Customer Logins

Obtain the data you need to make the most informed decisions by accessing our extensive portfolio of information, analytics, and expertise. Sign in to the product or service center of your choice.

Customer Logins

ECONOMICS COMMENTARY

Mar 24, 2020

Flash UK PMI signals record slump in business activity as coronavirus hits

- Flash Composite PMI™ falls to all-time low of 37.1 as business reports widespread COVID-19 impact

- Future business sentiment drops to record low and employment falls at steepest rate in 11 years

- Service sector hit especially hard by collapse in demand

The flash PMI surveys for March highlight how the COVID-19 outbreak has already dealt the UK economy its hardest blow since data were first available over 20 years ago. With additional measures to contain the spread of the virus set to further paralyse large parts of the economy in coming months, a recession of a scale we have not seen in modern history is looking increasingly likely.

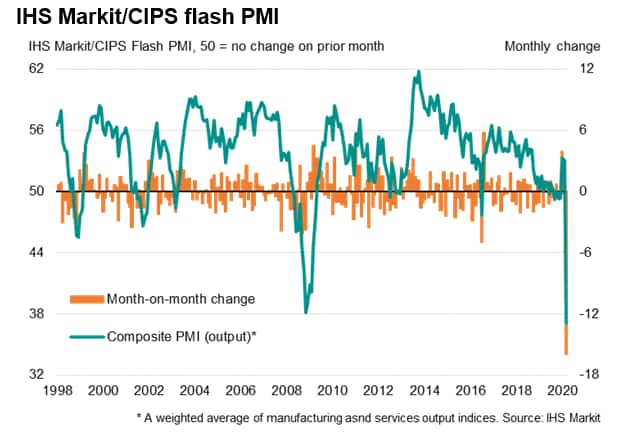

The combined monthly decline in output across manufacturing and services exceeded that seen even at the height of the global financial crisis, the composite IHS Markit/CIPS flash PMI falling some 16 points, dropping by more than three times than ever seen before, to reach a new low of 37.1. The prior low of 38.1 was recorded in November 2008.

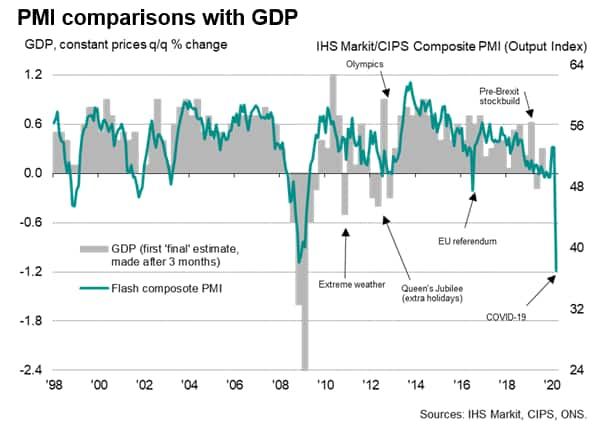

Historical comparisons of the PMI with GDP indicate that the march survey reading is consistent with GDP falling at a quarterly rate of 1.5-2.0%. This March decline is sufficiently large to push the economy into a contraction in the first quarter, vastly offsetting the modest growth seen in the first two months of the year, when the economy enjoyed an initial post-election rebound.

Service sector leads the downturn

Besides a few pockets of the economy which saw demand surge higher due to the coronavirus outbreak, vast swathes of the economy saw sharp downturns in demand and activity, with many suffering the sharpest declines ever recorded by the survey.

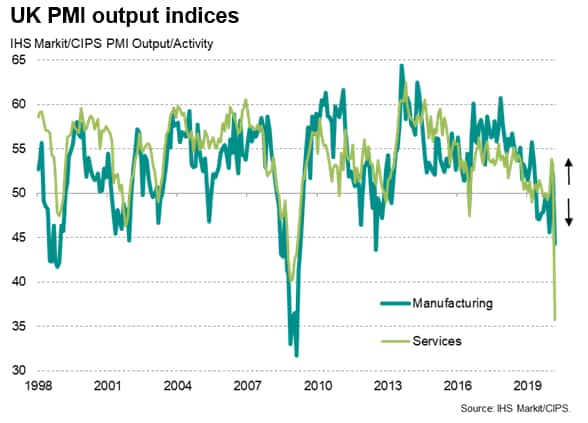

The steepest decline was recorded in the services sector, where business activity collapsed at a rate not previously recorded since data for the sector were first collected in 1996 as measures to halt the spread of the coronavirus caused demand to slump. By far the most severe downturns in activity were recorded in consumer-facing sectors, notably hotels, restaurants and other leisure-based activities such as sports centres, gyms and hair salons, which collectively reported the steepest fall in activity seen since the survey began.

The virus was also cited as a factor behind record downturns in the transport and travel sector, as well as in the vast business services sector, which covers a wide spectrum of firms from accounting and advertising through to consultancies and recruitment agencies. The financial services sector meanwhile reported its steepest decline since early 2009. Even computing and IT services reported a rare drop in activity.

Small pockets of manufacturing growth

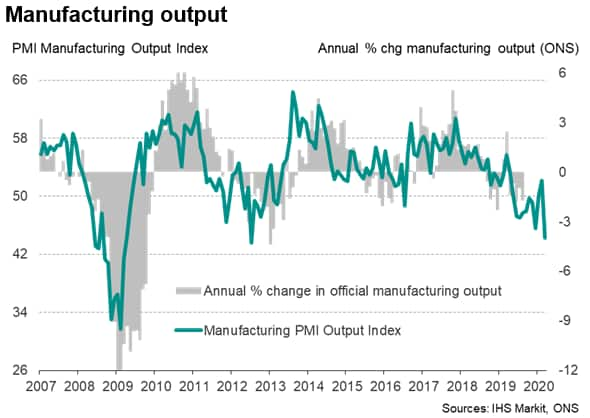

While the manufacturing downturn was less severe than recorded in services, output nonetheless fell at the sharpest rate since July 2012, the rate of decline exceeded only once since the global financial crisis. Only producers in the food & drink and chemicals & plastics sectors reported any growth of output in March. The former reported higher demand due to stockpiling by households while the latter saw increased virus-fighting activity in the pharmaceutical sector.

While some evidence of stockpiling was also evident in other manufacturing sectors, any such boost was dwarfed by a either downturn in demand or constraints on production due to supply shortages or staffing issues. The steepest decline was recorded in the car and other transport manufacturing sector, which has suffered some of the most severe supply chain problems.

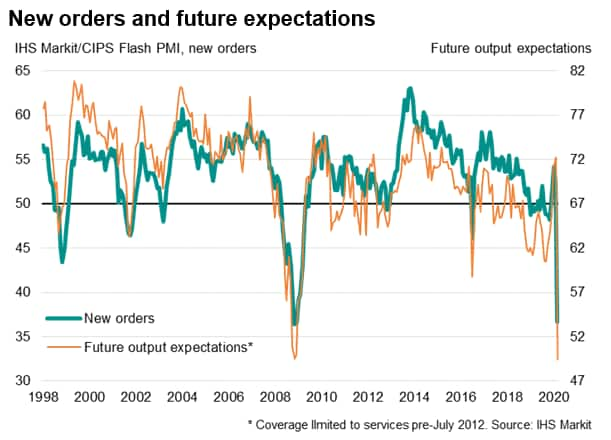

Future output optimism collapses

Other indicators pointed to similar signs of distress. New orders across manufacturing and services fell at the second-sharpest rate seen since comparable data were first available in 1998, the decline exceeded only by that suffered at the height of the global financial crisis in late-2008, while business expectations for the year ahead crumbled to the lowest seen since data for this series was available in 2012 by a wide margin. Expectations in the service sector, for which data are available back to 1996, were the worst in the survey history, but manufacturing sentiment about the year ahead also collapsed to a new low.

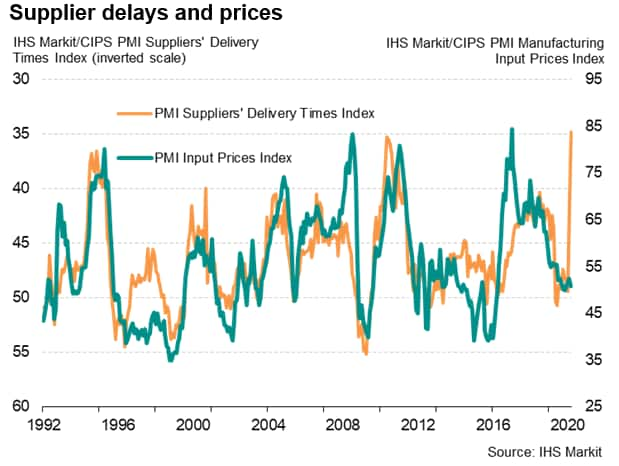

Supply chains see record delays, but prices fall

The March survey findings clearly illustrates how an initial supply shock, which continued to manifest itself in March through the longest lengthening of suppliers' delivery times on record, has also developed rapidly into a demand shock.

The slump in demand meant that longer delivery delays and shortages of goods did not feed through to higher prices, as would normally be seen when supply delays become more prevalent. In fact, manufacturing input prices rose in March at the slowest rate since last November, barely rising on average, as suppliers faced falling global demand for many commodities and inputs.

Service sector costs also rose at a weaker rate, in part reflecting lower staff costs. Average prices charged for goods and services meanwhile fell for the first time for almost five years as firms cut prices to help boost sales.

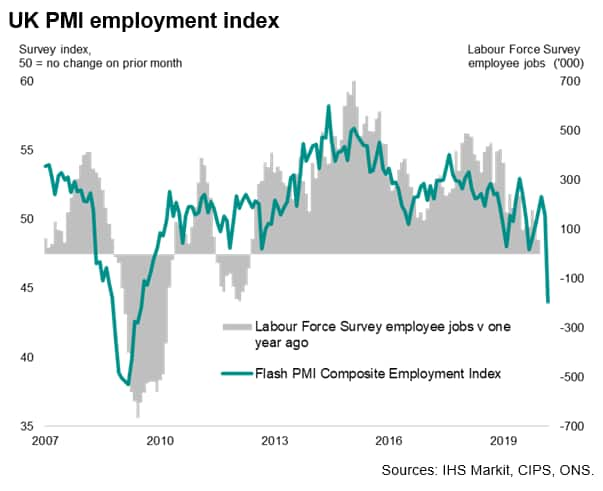

Job losses highest for nearly 11 years

The slump in demand and collapse in business expectations for the year ahead led to fierce job losses. Employment across manufacturing and services fell in March to an extent not seen since July 2009. Both manufacturers and service providers cut jobs at the fastest rates since July 2009.

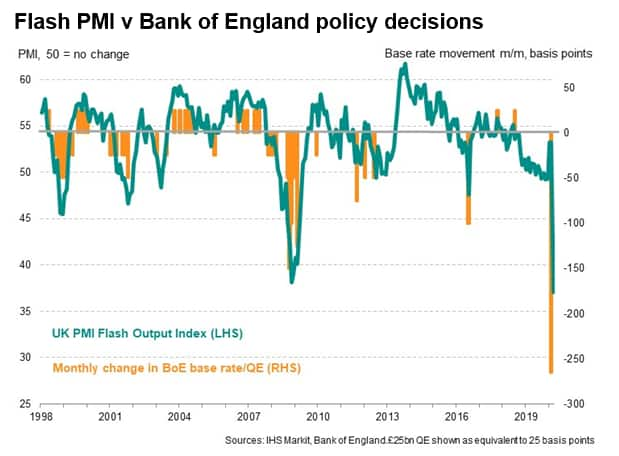

Policy response

The survey data were collected between the 12th and 20th March, with the majority of responses therefore received before the Bank of England's emergency measures, which in March have so far seen a slashing of interest rates to a record low of 0.1% and a new round of asset purchases of £200bn (representing a bigger one-off stimulus than seen even during the global financial crisis). The US has also seen a mix of measures from the government to help businesses and household weather the storm of the coronavirus. However, with increasingly tough measures to contain the virus outbreak, such as business closures and potential lockdowns, likely to further hit demand in coming weeks and months, the worst of the economic impact from the coronavirus is yet to come.

The second quarter could clearly be far worse as these further measures take their toll. However, we are in largely uncharted territory here in terms of the rate of decline being seen in the economy, and there is a chance that actual GDP outturns could be far greater than indicated by the PMI, given the experience of the global financial crisis and the prevalence of full-scale business closures.

An exception could be the initial GDP data for the first quarter, which will include estimates for March and could therefore give a stronger reading than the PMI, given that January and February both saw reasonably robust growth in the UK economy.

Chris Williamson, Chief Business Economist, IHS

Markit

Tel: +44 207 260 2329

chris.williamson@ihsmarkit.com

© 2020, IHS Markit Inc. All rights reserved. Reproduction in whole

or in part without permission is prohibited.

Purchasing Managers' Index™ (PMI™) data are compiled by IHS Markit for more than 40 economies worldwide. The monthly data are derived from surveys of senior executives at private sector companies, and are available only via subscription. The PMI dataset features a headline number, which indicates the overall health of an economy, and sub-indices, which provide insights into other key economic drivers such as GDP, inflation, exports, capacity utilization, employment and inventories. The PMI data are used by financial and corporate professionals to better understand where economies and markets are headed, and to uncover opportunities.

This article was published by S&P Global Market Intelligence and not by S&P Global Ratings, which is a separately managed division of S&P Global.

{"items" : [

{"name":"share","enabled":true,"desc":"<strong>Share</strong>","mobdesc":"Share","options":[ {"name":"facebook","url":"https://www.facebook.com/sharer.php?u=http%3a%2f%2fprod.azure.ihsmarkit.com%2fmarketintelligence%2fen%2fmi%2fresearch-analysis%2fflash-uk-pmi-signals-record-slump-in-business-activity-as-coronavirus-hits.html","enabled":true},{"name":"twitter","url":"https://twitter.com/intent/tweet?url=http%3a%2f%2fprod.azure.ihsmarkit.com%2fmarketintelligence%2fen%2fmi%2fresearch-analysis%2fflash-uk-pmi-signals-record-slump-in-business-activity-as-coronavirus-hits.html&text=Flash+UK+PMI+signals+record+slump+in+business+activity+as+coronavirus+hits+%7c+S%26P+Global+","enabled":true},{"name":"linkedin","url":"https://www.linkedin.com/sharing/share-offsite/?url=http%3a%2f%2fprod.azure.ihsmarkit.com%2fmarketintelligence%2fen%2fmi%2fresearch-analysis%2fflash-uk-pmi-signals-record-slump-in-business-activity-as-coronavirus-hits.html","enabled":true},{"name":"email","url":"?subject=Flash UK PMI signals record slump in business activity as coronavirus hits | S&P Global &body=http%3a%2f%2fprod.azure.ihsmarkit.com%2fmarketintelligence%2fen%2fmi%2fresearch-analysis%2fflash-uk-pmi-signals-record-slump-in-business-activity-as-coronavirus-hits.html","enabled":true},{"name":"whatsapp","url":"https://api.whatsapp.com/send?text=Flash+UK+PMI+signals+record+slump+in+business+activity+as+coronavirus+hits+%7c+S%26P+Global+ http%3a%2f%2fprod.azure.ihsmarkit.com%2fmarketintelligence%2fen%2fmi%2fresearch-analysis%2fflash-uk-pmi-signals-record-slump-in-business-activity-as-coronavirus-hits.html","enabled":true}]}, {"name":"rtt","enabled":true,"mobdesc":"Top"}

]}