Customer Logins

Obtain the data you need to make the most informed decisions by accessing our extensive portfolio of information, analytics, and expertise. Sign in to the product or service center of your choice.

Customer Logins

ECONOMICS COMMENTARY

Apr 01, 2020

Manufacturing downturn deepens outside of China

- Global manufacturing PMI at second lowest since May 2009 as order book downturn accelerates

- China stabilises but rest of world sees biggest production fall since 2009

- Prices fall at sharpest pace for four years

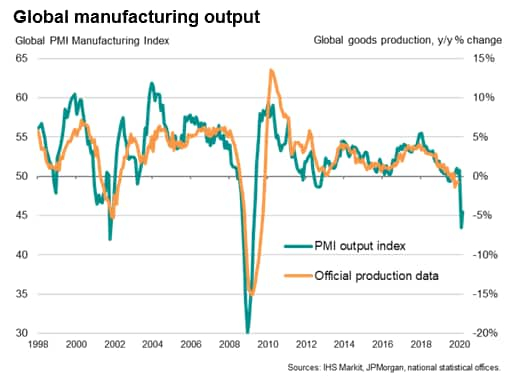

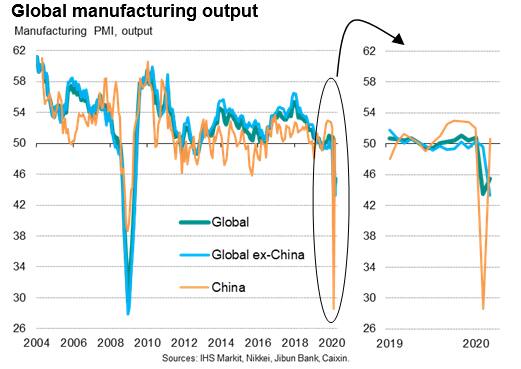

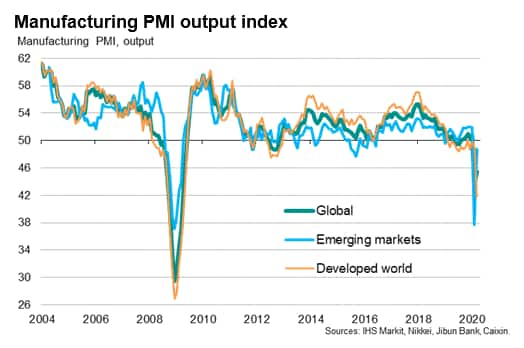

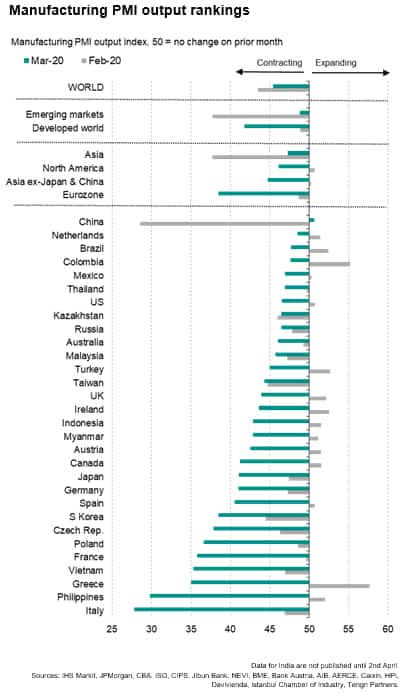

Global manufacturing orders fell at the steepest rate for 11 years in March as the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) outbreak continued to cause factory closures, disrupted supply chains and hit demand, according to PMI survey data. None of the 30 countries for which IHS Markit survey data are available reported higher order book volumes, while only China reported any month-on-month growth of output, merely reflecting a stabilising of production at a low base after suffering a record decline in February. Excluding China, global output fell at the sharpest rate since April 2009.

New orders fall at fastest rate since 2009

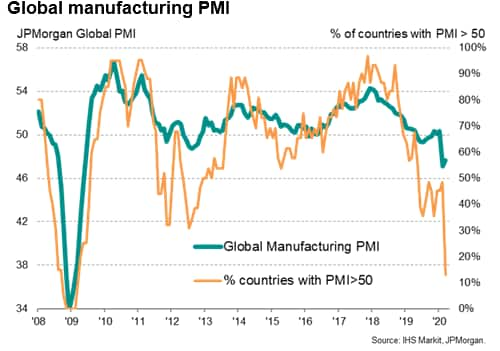

The JPMorgan Global Manufacturing PMI, compiled by IHS Markit from its business surveys, recorded 47.6 in March, up from 47.1 in February. Although indicating a mild easing in the rate of decline, the latest reading is the second lowest since May 2009 and signalled a steep deterioration in the health of worldwide manufacturing for a second successive month.

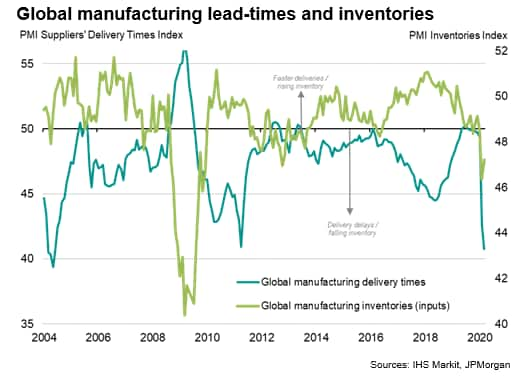

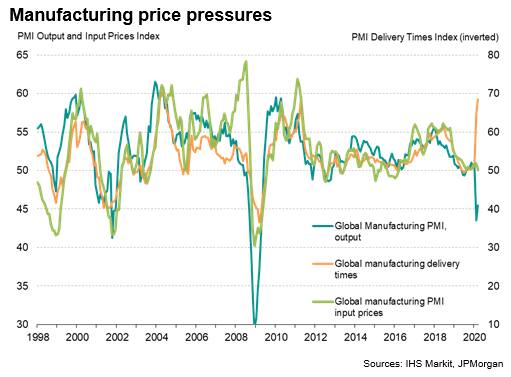

However, even this weak reading masks the scale of the downturn in manufacturing, as the PMI includes a measure of supplier performance as one of its five components . Longer deliveries are normally a sign of a busier economy, and hence contribute positively to the PMI. However, at present, delivery times are lengthening because of virus-related shutdowns, according to survey replies, providing a false 'boost' to the PMI. Importantly, both output and new orders fell at faster rates than the headline PMI, providing better insights into the true scale and depth of the recent collapse in production and demand. The monthly drop in worldwide factory production was the second steepest since April 2009, while the drop in new orders was the largest since March 2009.

Worldwide trade flows also continued to deteriorate at the fastest rate for over a decade. New export orders placed at manufacturers fell globally to a degree not seen since April 2009.

Delivery delays highest since 2004 as pandemic disrupts supply chains

The worldwide drop in production, orders and trade flows was predominantly linked to factory closures, in turn connected to measures to contain the COVID-19 pandemic, as well as slumping demand and input shortages. Supply chain delays rose to the highest recorded since global production growth boomed in 2004. However, whereas 2004 saw shortages develop as a result of strong demand, the latest delivery times lengthening was due to delays in the provision of inputs due to extended virus-related factory shutdowns. Global inventory holdings of inputs fell sharply again, largely as a result of the supply limitations.

Jobs under pressure as optimism slides to record low

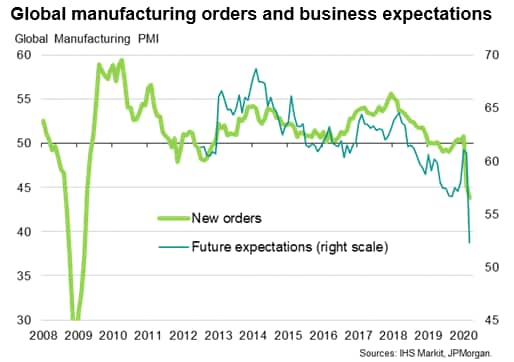

Worries about the impact of the pandemic meant manufacturers' expectations of output over the coming year plunged to a record extent, taking the degree of optimism well below anything previously seen since comparable data were first available in 2012.

Employment fell as a consequence of the darkening picture, though the rate of job losses eased slightly compared to February. In some cases, job numbers had been held steady despite the recent drops in orders due to government incentives to retain staff. However, it remains unclear how long workers will be retained if the outlook worsens further.

Slumping demand pushes prices lower

A lack of demand led to increased price discounting during March, causing average prices charged for goods to fall at the fastest rate since December 2015.

Average input prices were meanwhile largely unchanged, representing the lowest rate of input cost inflation for four years, as suppliers also competed on price to sell stock. Lower oil prices also helped push down fuel and energy bills.

Charting the Input Prices index against suppliers' delivery times and output highlights how unusual the current situation is: longer deliveries are normally associated with higher prices, but at present a lack of demand due to collapsing production means such upward price pressure are largely absent.

China stabilises, but rest of world sees biggest production fall since 2009

The latest survey data were collected between 12th and 27th March, a time when China began easing some of the restrictions on travel and company closures but in the same period most other parts of the world, notably Europe and the US, began imposing stricter policies to prevent health services being overwhelmed by the COVID-19 outbreak. It was therefore no major surprise to see that, of the 30 countries for which PMI data have so far been published (data for India are released on 2nd April), only China reported a PMI output index in excess of 50, signalling a month-on-month increase in production.

However, although striking in terms of the extent of the rebound signalled by the rise in the Caixin PMI output index for mainland China (up from 28.6 to 50.6), the February reading had been by far the lowest in the near 16-year history of the survey. The latest reading therefore indicates that production in China has only risen very marginally after plunging in February, which hints at only a limited impact from factories reopening after virus-related closures in February.

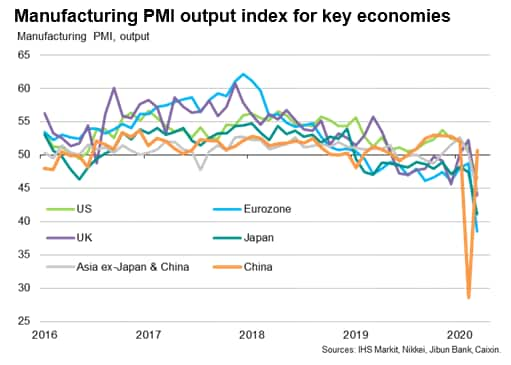

If we exclude China from the calculations, global output fell at the sharpest rate since April 2009, with the steepest decline reported in Italy, where factories have been especially hard hit due to closures resulting from the COVID-19 outbreak.

The steadying of production in China helped lift the emerging market PMI output index from the 11-year low seen in February, but output nevertheless still contracted for a second month in a row. The downturn in developed world output meanwhile intensified, with production slumping to the greatest extent since April 2009.

Looking at the major developed economies, US and eurozone production fell at the steepest rates since early 2009, with the latter seeing an especially severe downturn. Japan meanwhile recorded the sharpest decline since the earthquakes and tsunamis of 2011 and the UK suffered the biggest slump since mid-2012.

Weakness ahead

With many factories around the world likely to remain closed into April, coming months could see further declines in the global PMI. Note also that the forward-looking new orders to inventory ratio sank to a new post global financial crisis low in March, hinting strongly that the production trend will deteriorate further in April.

Looking further ahead, supply constraints should ease (notably from China) when more factories come back online as restrictions to contain the pandemic ease, helping lift production at other firms. However, the concern is that demand will continue to wither, as both business and consumers retrench globally with lockdowns persisting for potentially prolonged periods.

Finally, a reminder on survey methodology as we wait to see turning points. The rebound in the PMI for China, and experience from 2008-9, highlights how data tracking month-on-month changes in variables such as production will rarely stay at historically low levels for long during times of especially steep drops in production. However, it is important to bear in mind that the indices need to move significantly above 50 to indicate any recovery of the output lost in the prior month: a reading of 50 (signalling no change) would be achieved even if all factories closed one month and remained closed the following month.

Chris Williamson, Chief Business Economist, IHS

Markit

Tel: +44 207 260 2329

chris.williamson@ihsmarkit.com

© 2020, IHS Markit Inc. All rights reserved. Reproduction in whole or in part without permission is prohibited.

Purchasing Managers' Index™ (PMI™) data are compiled by IHS Markit for more than 40 economies worldwide. The monthly data are derived from surveys of senior executives at private sector companies, and are available only via subscription. The PMI dataset features a headline number, which indicates the overall health of an economy, and sub-indices, which provide insights into other key economic drivers such as GDP, inflation, exports, capacity utilization, employment and inventories. The PMI data are used by financial and corporate professionals to better understand where economies and markets are headed, and to uncover opportunities.

This article was published by S&P Global Market Intelligence and not by S&P Global Ratings, which is a separately managed division of S&P Global.

{"items" : [

{"name":"share","enabled":true,"desc":"<strong>Share</strong>","mobdesc":"Share","options":[ {"name":"facebook","url":"https://www.facebook.com/sharer.php?u=http%3a%2f%2fprod.azure.ihsmarkit.com%2fmarketintelligence%2fen%2fmi%2fresearch-analysis%2fmanufacturing-downturn-deepens-outside-of-china-april2020.html","enabled":true},{"name":"twitter","url":"https://twitter.com/intent/tweet?url=http%3a%2f%2fprod.azure.ihsmarkit.com%2fmarketintelligence%2fen%2fmi%2fresearch-analysis%2fmanufacturing-downturn-deepens-outside-of-china-april2020.html&text=Manufacturing+downturn+deepens+outside+of+China+%7c+S%26P+Global+","enabled":true},{"name":"linkedin","url":"https://www.linkedin.com/sharing/share-offsite/?url=http%3a%2f%2fprod.azure.ihsmarkit.com%2fmarketintelligence%2fen%2fmi%2fresearch-analysis%2fmanufacturing-downturn-deepens-outside-of-china-april2020.html","enabled":true},{"name":"email","url":"?subject=Manufacturing downturn deepens outside of China | S&P Global &body=http%3a%2f%2fprod.azure.ihsmarkit.com%2fmarketintelligence%2fen%2fmi%2fresearch-analysis%2fmanufacturing-downturn-deepens-outside-of-china-april2020.html","enabled":true},{"name":"whatsapp","url":"https://api.whatsapp.com/send?text=Manufacturing+downturn+deepens+outside+of+China+%7c+S%26P+Global+ http%3a%2f%2fprod.azure.ihsmarkit.com%2fmarketintelligence%2fen%2fmi%2fresearch-analysis%2fmanufacturing-downturn-deepens-outside-of-china-april2020.html","enabled":true}]}, {"name":"rtt","enabled":true,"mobdesc":"Top"}

]}