Customer Logins

Obtain the data you need to make the most informed decisions by accessing our extensive portfolio of information, analytics, and expertise. Sign in to the product or service center of your choice.

Customer Logins

ECONOMICS COMMENTARY

Sep 02, 2021

Global manufacturing growth at lowest for 14 months as supply chains worsen amid Delta variant spread, price pressures hold close to decade highs

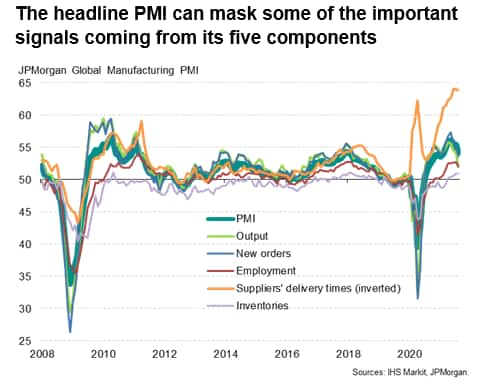

A mild decline in the headline global PMI masks a more worrying downturn in manufacturing production revealed by the survey's sub-indices. These sub-indices also add colour to what has caused the downturn in production growth and the consequences of the slowdown.

Digging deeper than the headline PMI

Global manufacturing remained beset by unprecedented supply issues in July, which constrained output and drove prices higher.

The headline JPMorgan Global Manufacturing PMI fell from 55.4 in July to 54.1 in August, a 1.3 index point fall indicating only a modest cooling in an otherwise still-solid rate of improvement of business conditions worldwide. However, dig deeper into the sub-indices from the survey and a more worrying picture emerges.

First. It's important to remember that the PMI is a composite indicator derived from five survey sub-indices. Three of these - suppliers' delivery times, employment and inventories, can mask the underling signals of changing demand and production from the new orders and output sub-indices. Hence we need to look at the PMI's components individually to get a better picture of what's really happening beneath the headline number.

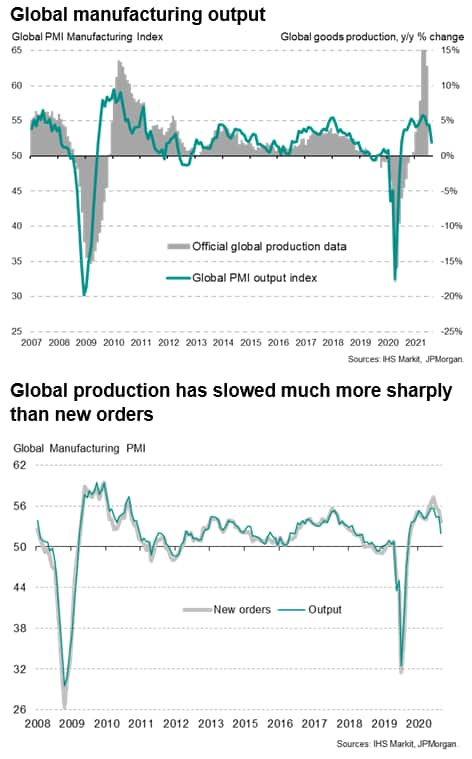

Marked production slowdown linked only partly to weaker demand growth

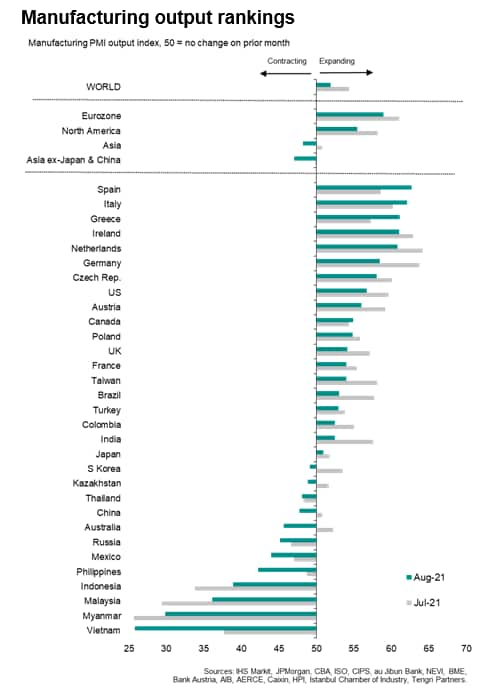

The first signal we look at is from the output index, which gives the purest indication of changing production trends in the economy, and which tends to exhibit a strong correlation with official manufacturing output data. It is notable that the global manufacturing output index fell much more sharply than the headline PMI in August, down 2.5 points to 51.9, its lowest since June of last year.

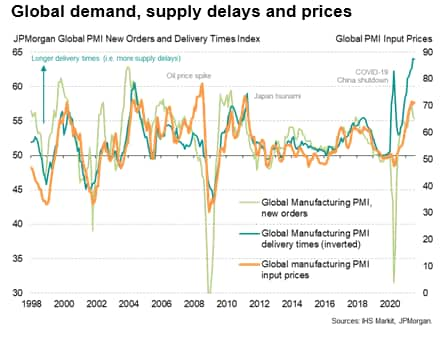

Some of the slowdown in production is related to weaker growth of demand, as witnessed by the global PMI survey's new orders index slipping to 53.6, its lowest since last August. But, as the new orders index remained higher than the output index in August, the slowing in demand growth appears to be only part of the story.

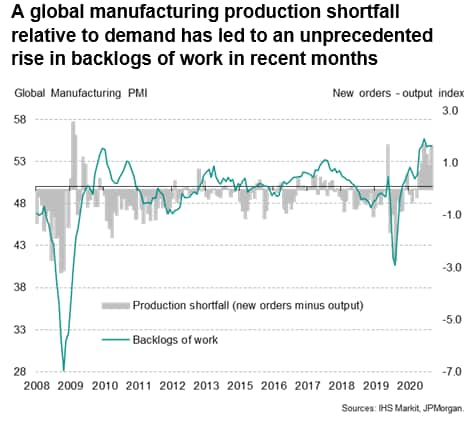

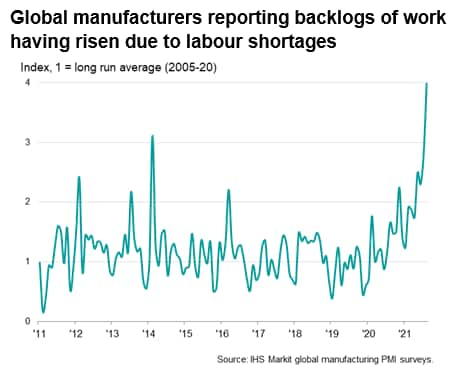

Production shortfall leads to unprecedented rise in backlogs of work

In fact, new orders inflows are growing faster than production to an extent not exceeded since 2009, pointing to a marked shortfall of production relative to demand that has persisted since March. This production shortfall has led to a period of unprecedented growth in backlogs of uncompleted work in recent months ( read more about how to interpret and use our backlogs of work index here).

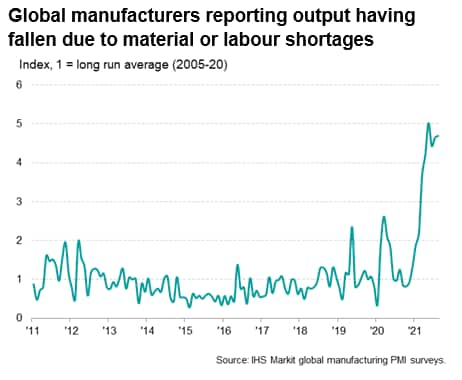

Output constrained by shortages

Hints of what's causing production to slow at a faster rate than demand can be found in the anecdotal evidence provided by companies when responding to the PMI surveys. This evidence reveals a widespread issue with material supply shortages and, in some cases, labour shortages, which have curbed companies' abilities to expand production. The analysis of survey responses suggests that the number of companies reporting lower production due to staff or materials shortages is running at around five times the historical norm.Output constrained by shortagesHints of what's causing production to slow at a faster rate than demand can be found in the anecdotal evidence provided by companies when responding to the PMI surveys. This evidence reveals a widespread issue with material supply shortages and, in some cases, labour shortages, which have curbed companies' abilities to expand production. The analysis of survey responses suggests that the number of companies reporting lower production due to staff or materials shortages is running at around five times the historical norm.

Looking at labour shortages, analysis of anecdotal evidence provided by survey respondents reveals that the number of companies reporting that backlogs of work are rising due to a labour shortage is running at four times the long tun average, a multiple that is well above anything seen previously by the survey.

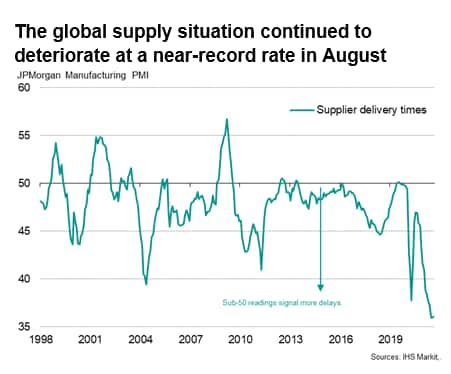

The material supply delays cited by PMI respondents are meanwhile also clearly illustrated by the PMI's suppliers' delivery times index, which in August signalled a lengthening of average supplier lead times of an extent exceeded only twice in the survey's 23-year history, those two occasions having been June and July of this year . You can find out more about the suppliers' delivery times index and its uses here.

Supply shortages linked to falling production in Asia and the Delta variant

If we delve deeper into the national survey data, it becomes clearer as to where the supply problems are emanating from.

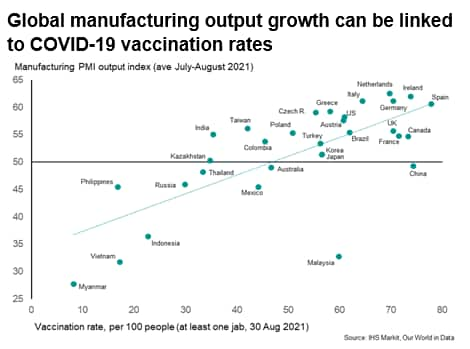

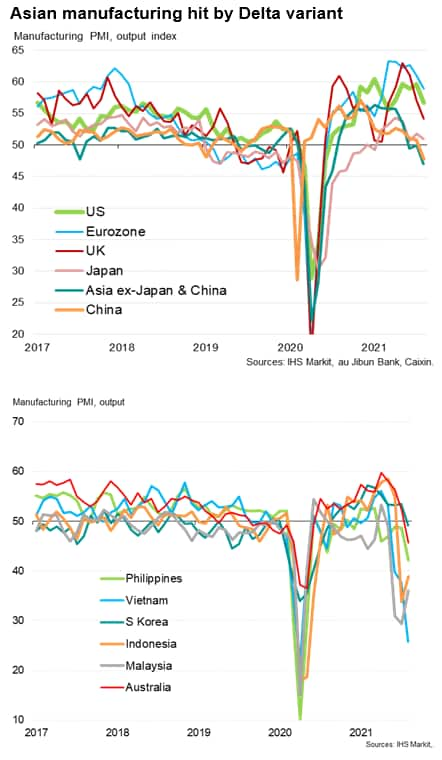

Production in Europe and the North America continued to rise at strong rates in August, albeit with some cooling in the rate of expansion evident in the US, Eurozone and UK. But it's a much different picture in many other economies, where lower COVID-19 vaccination rates have meant virus-fighting restrictions have been intensified in recent months, dampening production capabilities, hitting demand and leading to sharp output falls.

Most notably, output fell in China during August at a rate not seen since the initial factory shutdowns of early-2020. Output in the rest of Asia (excluding both China and Japan) meanwhile fell at a pace not seen since last July, led by an especially sharp drop in factory output in Vietnam. Steep declines were also reported in Malaysia, Indonesia, the Philippines and Myanmar. Declines in production were also seen in Thailand and South Korea, with a severe drop in Australia adding to a worsening broader APAC picture.

Supply chain delays are most pronounced in the West, driving prices higher

With many Asian factories exporting goods to the rest of the world, this lack of production has once again hit shipments of vital components to the rest of the world during August. Hence delivery delays have been most widely felt in the US and Europe (and, in the UK, new Brexit regulations have exacerbated the broader global supply chain squeeze).

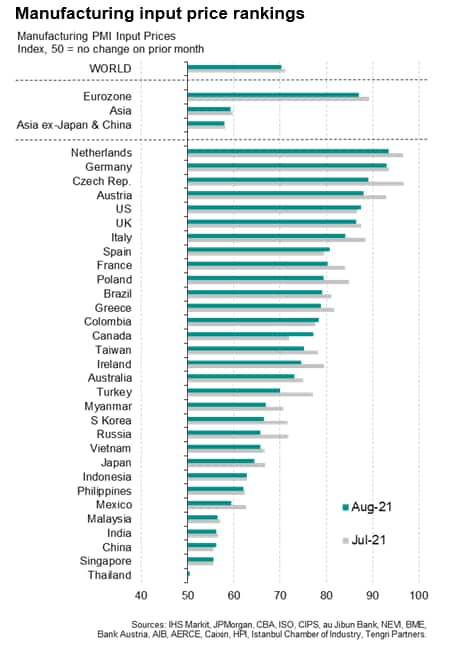

This shortage of supply relative to demand has resulting in sharply higher prices for many inputs. The survey's manufacturing input price gauge has been hitting ten-year highs in recent months, albeit suggesting some mild easing in the rate of inflation to a four-month low in August.

Not surprisingly, the highest materials price pressures have been seen in countries with the worst supply situations and where demand is especially strong, in part due to pandemic related stimulus, namely Europe and the US.

Higher prices for longer

The August PMI data therefore demonstrate how global production is currently being constrained by supply shortages, linked to a large extent to a renewed downturn in production in Asia Pacific, which is in turn attributable to the increased spread of the COVID-19 Delta variant in countries with low vaccination rates.

The consequence is a further rise in supplier prices for components and raw materials to manufacturers, which is likely to pass through to a more sustained increase in consumer prices in many countries than previously anticipated by many observers. The precise duration of these higher prices will inevitably hinge on a combination of demand-pull pressures and supply-push pressures, all of which will be monitored in coming months by the PMI sub-indices.

Chris Williamson, Chief Business Economist, IHS Markit

Tel: +44 207 260 2329

chris.williamson@ihsmarkit.com

© 2021, IHS Markit Inc. All rights reserved. Reproduction in whole

or in part without permission is prohibited.

Purchasing Managers' Index™ (PMI™) data are compiled by IHS Markit for more than 40 economies worldwide. The monthly data are derived from surveys of senior executives at private sector companies, and are available only via subscription. The PMI dataset features a headline number, which indicates the overall health of an economy, and sub-indices, which provide insights into other key economic drivers such as GDP, inflation, exports, capacity utilization, employment and inventories. The PMI data are used by financial and corporate professionals to better understand where economies and markets are headed, and to uncover opportunities.

This article was published by S&P Global Market Intelligence and not by S&P Global Ratings, which is a separately managed division of S&P Global.

{"items" : [

{"name":"share","enabled":true,"desc":"<strong>Share</strong>","mobdesc":"Share","options":[ {"name":"facebook","url":"https://www.facebook.com/sharer.php?u=http%3a%2f%2fprod.azure.ihsmarkit.com%2fmarketintelligence%2fen%2fmi%2fresearch-analysis%2fglobal-manufacturing-growth-at-lowest-for-14-months-as-supply-chains-worsen-amid-delta-variant-spread-Sep21.html","enabled":true},{"name":"twitter","url":"https://twitter.com/intent/tweet?url=http%3a%2f%2fprod.azure.ihsmarkit.com%2fmarketintelligence%2fen%2fmi%2fresearch-analysis%2fglobal-manufacturing-growth-at-lowest-for-14-months-as-supply-chains-worsen-amid-delta-variant-spread-Sep21.html&text=Global+manufacturing+growth+at+lowest+for+14+months+as+supply+chains+worsen+amid+Delta+variant+spread%2c+price+pressures+hold+close+to+decade+highs+%7c+S%26P+Global+","enabled":true},{"name":"linkedin","url":"https://www.linkedin.com/sharing/share-offsite/?url=http%3a%2f%2fprod.azure.ihsmarkit.com%2fmarketintelligence%2fen%2fmi%2fresearch-analysis%2fglobal-manufacturing-growth-at-lowest-for-14-months-as-supply-chains-worsen-amid-delta-variant-spread-Sep21.html","enabled":true},{"name":"email","url":"?subject=Global manufacturing growth at lowest for 14 months as supply chains worsen amid Delta variant spread, price pressures hold close to decade highs | S&P Global &body=http%3a%2f%2fprod.azure.ihsmarkit.com%2fmarketintelligence%2fen%2fmi%2fresearch-analysis%2fglobal-manufacturing-growth-at-lowest-for-14-months-as-supply-chains-worsen-amid-delta-variant-spread-Sep21.html","enabled":true},{"name":"whatsapp","url":"https://api.whatsapp.com/send?text=Global+manufacturing+growth+at+lowest+for+14+months+as+supply+chains+worsen+amid+Delta+variant+spread%2c+price+pressures+hold+close+to+decade+highs+%7c+S%26P+Global+ http%3a%2f%2fprod.azure.ihsmarkit.com%2fmarketintelligence%2fen%2fmi%2fresearch-analysis%2fglobal-manufacturing-growth-at-lowest-for-14-months-as-supply-chains-worsen-amid-delta-variant-spread-Sep21.html","enabled":true}]}, {"name":"rtt","enabled":true,"mobdesc":"Top"}

]}