Customer Logins

Obtain the data you need to make the most informed decisions by accessing our extensive portfolio of information, analytics, and expertise. Sign in to the product or service center of your choice.

Customer Logins

ECONOMICS COMMENTARY

May 03, 2022

Worldwide factory output falls for first time since June 2020 as supply conditions worsen

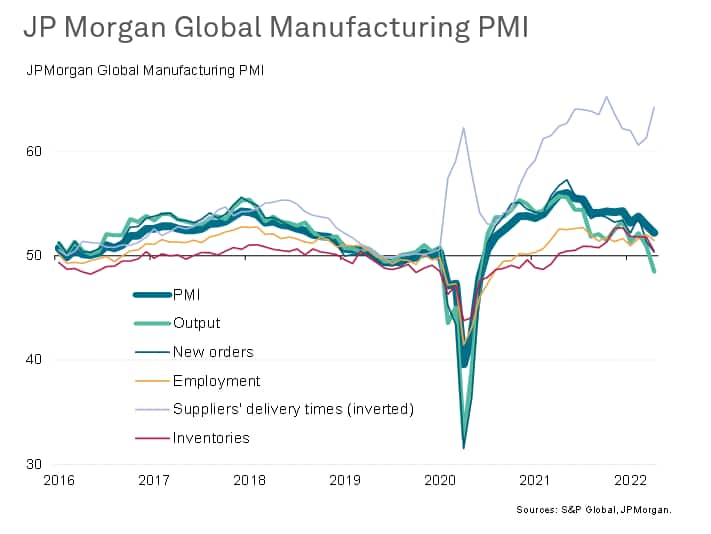

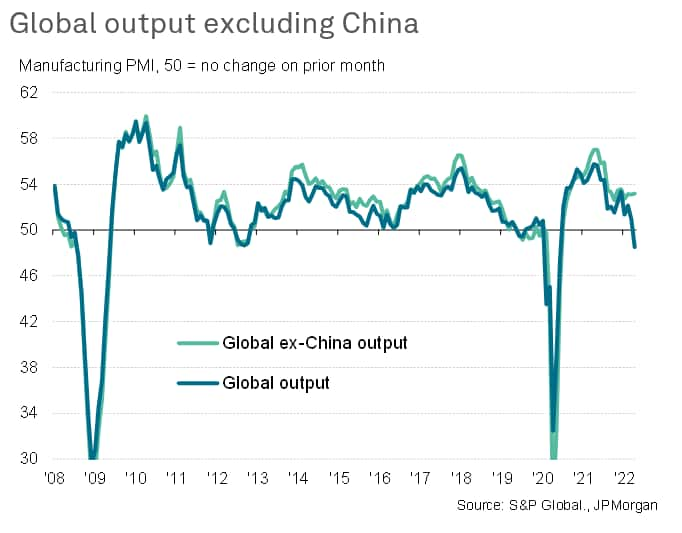

The JPMorgan Manufacturing Purchasing Managers' Index™ (PMI™), compiled by S&P Global, fell from 52.9 in March to a 20-month low of 52.2 in April. The deterioration in the performance of the goods-producing sector was led by a renewed decline in production, which fell for the first time since June 2020, thanks principally by a steeping rate of output loss in mainland China amid fresh lockdown measures. Encouraging, excluding China, global output growth accelerated slightly in April. However, China's downturn, combined with disruptions caused by the Ukraine war, also led to a worsening global supply situation, which in turn pushed price pressures higher and led to a further drop in global business expectations for output in the year ahead.

In this analysis we look beyond the headline PMI to provide deeper insights into the current health of manufacturing around the world and the outlook for coming months.

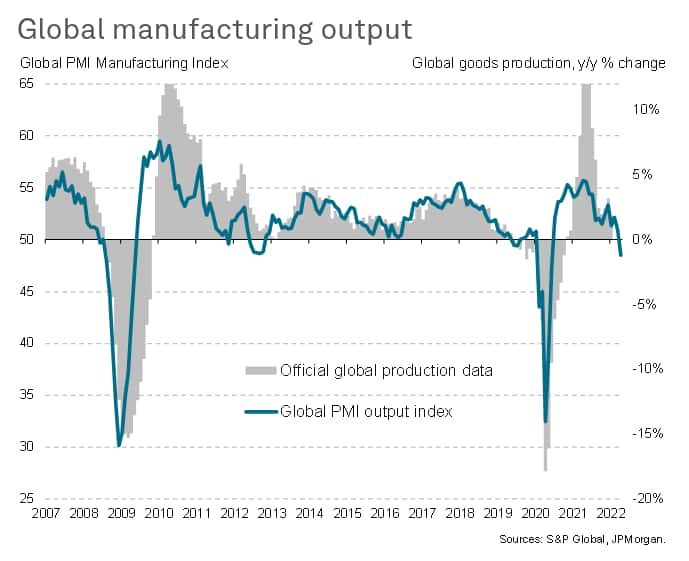

Global factory output falls in April

The weakest of the PMI's five components in April was the Output Index, which fell from 50.9 in March to 48.5. These readings indicate that the global manufacturing sector went from a position of near-stalled output at the end of the first quarter to one of declining production at the start of the second quarter. This represents the first global contraction since June 2020, during the initial phase of the pandemic. Prior to the pandemic, output has not fallen at this rate since the global financial crisis.

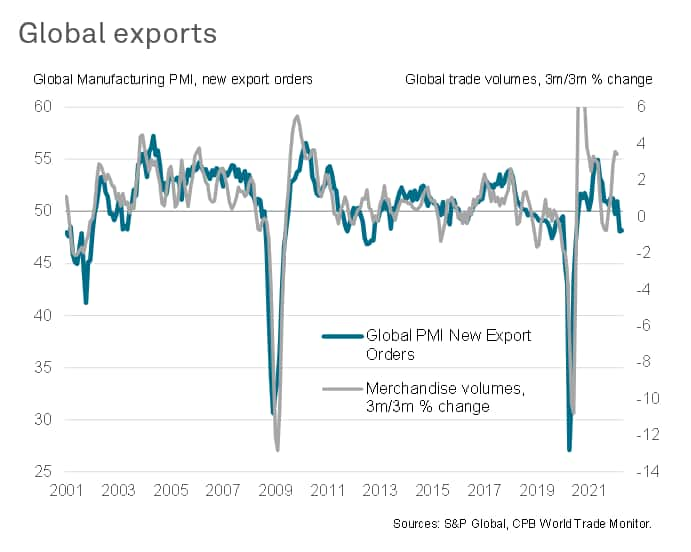

Global trade firmly in decline

April also saw global new orders almost stall, registering only a marginal increase which was the smallest since June 2020. The demand slowdown was due in part to a second consecutive monthly drop in global trade flows. The past two months have seen the sharpest loss of new export orders since the early months of the pandemic.

Mainland China reporting worst growth spell on record

A principal driver of the slowdown in output and demand was a severe downturn in mainland China, where output and new orders fell sharply for a second month, in both cases with the rate of decline accelerating to the fastest since the initial pandemic decline seen in February 2020. However, whereas the initial pandemic decline in China merely lasted one month, China has now reported falling output in three of the past four months, with the latest back-to-back declines representing the worst production performance since data collection began in 2004.

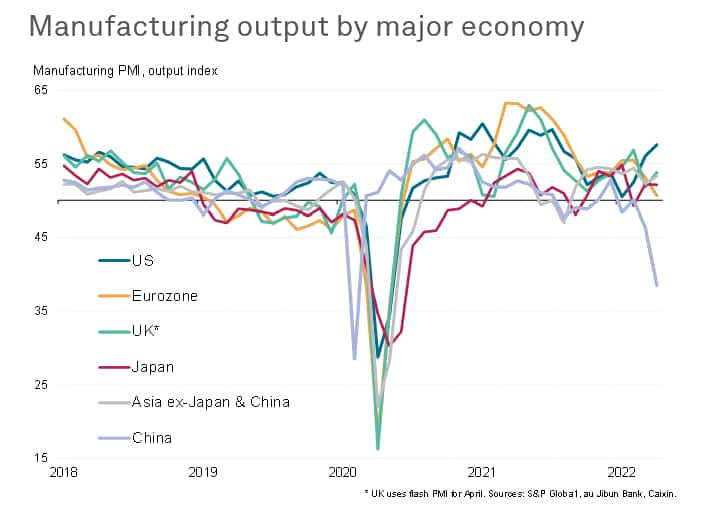

Growth more resilient outside of China

It's a more encouraging picture outside of China. Excluding mainland China, global output growth in fact accelerated marginally in April to the fastest since December, albeit remaining well below the average pace recorded last year. The improvement was driven by the US, where output rose at the strongest rate since July of last year, and to a lesser extent the UK, which also reported improved growth. Japan meanwhile reported a sustained, though still sluggish, recovery from a brief Omicron-related downturn in February, while the rest of Asia as a whole also reported an improvement on March's slowdown.

However, in addition to the downturn in China, the overall global expansion was weighed on by a near-stalling of production in the eurozone, which was in turn fueled by a renewed decline in German production, reflecting the impact of the Ukraine war on those economies closest - both geographically and economically - to the conflict.

Note that PMI data for Russia are not updated for April until 4th May, but March's data had shown Russia registering the steepest contraction of all economies covered by the PMI, and one of the sharpest downturns on record, mainly reflecting the impact of sanctions following the invasion of Ukraine.

Supply chain delays worsen

A further visible impact of the lockdowns in China was evident in supply chains. Average supplier delivery times lengthened in April at a rate exceeded only once - last October - in the history of the PMI surveys. The worsening supply chain performance was driven by a severe lengthening of lead times in China, though delivery delays also worsened in the US and remained especially widespread in Europe.

The overall supply chain situation therefore remains one of supply delays continuing to be reported to an extent far exceeding anything previously recorded prior to the pandemic, albeit with delays somewhat less prevalent than the average seen in 2021.

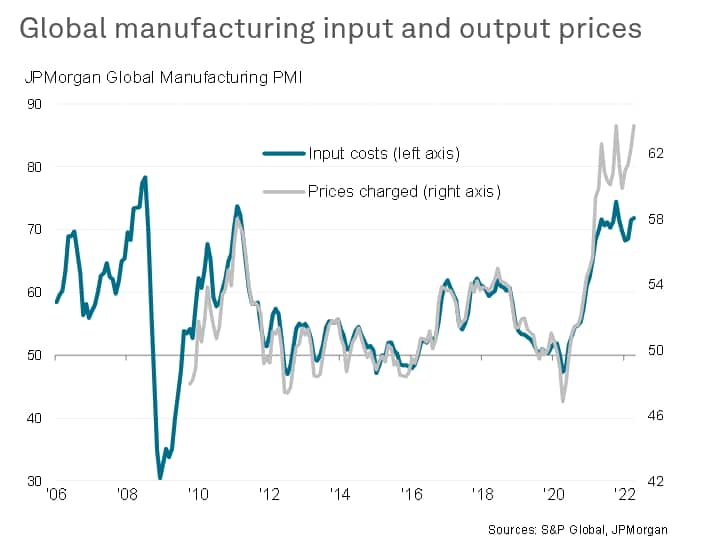

Price indicators signaling rising inflationary pressures

The worsening supply situation led to further upward pressure on prices, with global manufacturing input price inflation accelerating for a third successive month in April to register an increase exceeded only once - last October - in the past 11 years. These additional cost pressures, as well as further wage costs and shipping prices, were passed on to customers in the form of a steepening rate of increase in average selling prices for manufactured goods, the rate of inflation for which rose to the joint-highest on record (since 2009).

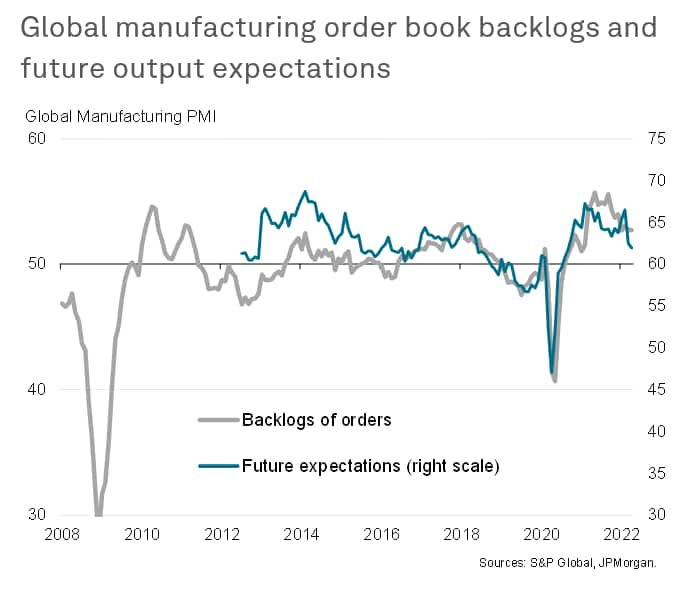

Future expectations deteriorate to 19-month low

Looking ahead, the further surge in cost pressures and supply delays, combined with geopolitical risks linked to Russia, led to a gloomier outlook.

On one hand, a further rise in backlogs of work reflected the fact that supply delays meant new orders growth continued to run ahead of production growth globally in April, therefore suggesting some near-term support to production in coming months if supply constraints ease. On the other hand, the rises in backlogs in March and April have been the smallest since early 2021, even if China is excluded. This reduced rate of growth of uncompleted orders hints at a broader slowing production trend.

Similarly, while future output expectations remained in positive territory in April, the degree of optimism was the lowest since September 2020, having fallen sharply since the start of the year. Companies' concerns were generally focused on rising prices and the potential hit to demand, as well as on-going supply constraints and increasing concerns about future economic growth prospects.

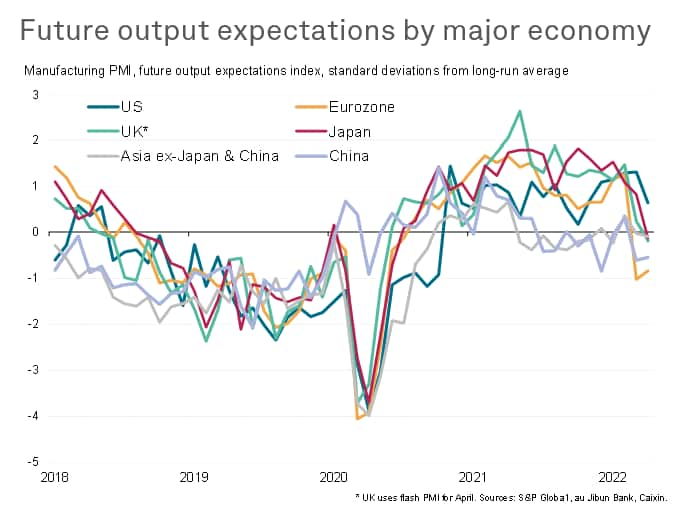

Only the US now sees future optimism above long run average

Future output expectations among the major economies are holding up best relative to their long run averages in the US, though even here prospects are their gloomiest since last October. Sentiment has meanwhile fallen below long run averages in the eurozone and China over the past two months, with only marginal uplifts seen in April, and have now slipped below long run means in the UK, Japan and the rest of Asia (excluding Japan and China).

Outlook

The situations in China and Russia will be key to the outlook. In terms of China, lockdowns due to the government's zero-covid policy have led to a more severe manufacturing disruption amid the Omicron wave than seen during the initial COVID-19 outbreak in 2020. The current downturn in China is showing signs of extending the global supply chain crisis, and we may not yet be seeing the full impact of these disruptions. The longer the lockdowns continue, the more strained the closed-loop systems at facilities in and near China's ports will become, especially as supply into these 'bubbles' is showing signs of deteriorating.

Russia's invasion of Ukraine is meanwhile not only disrupting supply chains in Europe, notably Germany, but is also putting marked upward pressure on energy availability and prices. The conflict also shows no signs of ending soon, adding to downside growth risks both in Europe and in the wider global economy and upside inflation risks.

A third unknown is the policy reaction to rising inflation. While annual rates of inflation may soon start to fall, reflecting the fact that inflation is measured on a year-on-year basis, the supply disruption out of China and the Ukraine war add to risks of more persistent elevated readings through the year, raising the likelihood of more aggressive central bank policy tightening. The extent to which this plays out will of course depend on the durability of demand in this environment.

PMI updates to track the course of supply and demand over the coming months are available to all. Sign up to receive updated commentary in your inbox here.

Chris Williamson, Chief Business Economist, S&P Global Market Intelligence

Tel: +44 207 260 2329

chris.williamson@spglobal.com

© 2022, IHS Markit Inc. All rights reserved. Reproduction in whole

or in part without permission is prohibited.

Purchasing Managers' Index™ (PMI™) data are compiled by IHS Markit for more than 40 economies worldwide. The monthly data are derived from surveys of senior executives at private sector companies, and are available only via subscription. The PMI dataset features a headline number, which indicates the overall health of an economy, and sub-indices, which provide insights into other key economic drivers such as GDP, inflation, exports, capacity utilization, employment and inventories. The PMI data are used by financial and corporate professionals to better understand where economies and markets are headed, and to uncover opportunities.

This article was published by S&P Global Market Intelligence and not by S&P Global Ratings, which is a separately managed division of S&P Global.

{"items" : [

{"name":"share","enabled":true,"desc":"<strong>Share</strong>","mobdesc":"Share","options":[ {"name":"facebook","url":"https://www.facebook.com/sharer.php?u=http%3a%2f%2fprod.azure.ihsmarkit.com%2fmarketintelligence%2fen%2fmi%2fresearch-analysis%2fworldwide-factory-output-falls-for-first-time-since-june-2020-as-supply-conditions-worsen-May22.html","enabled":true},{"name":"twitter","url":"https://twitter.com/intent/tweet?url=http%3a%2f%2fprod.azure.ihsmarkit.com%2fmarketintelligence%2fen%2fmi%2fresearch-analysis%2fworldwide-factory-output-falls-for-first-time-since-june-2020-as-supply-conditions-worsen-May22.html&text=Worldwide+factory+output+falls+for+first+time+since+June+2020+as+supply+conditions+worsen+%7c+S%26P+Global+","enabled":true},{"name":"linkedin","url":"https://www.linkedin.com/sharing/share-offsite/?url=http%3a%2f%2fprod.azure.ihsmarkit.com%2fmarketintelligence%2fen%2fmi%2fresearch-analysis%2fworldwide-factory-output-falls-for-first-time-since-june-2020-as-supply-conditions-worsen-May22.html","enabled":true},{"name":"email","url":"?subject=Worldwide factory output falls for first time since June 2020 as supply conditions worsen | S&P Global &body=http%3a%2f%2fprod.azure.ihsmarkit.com%2fmarketintelligence%2fen%2fmi%2fresearch-analysis%2fworldwide-factory-output-falls-for-first-time-since-june-2020-as-supply-conditions-worsen-May22.html","enabled":true},{"name":"whatsapp","url":"https://api.whatsapp.com/send?text=Worldwide+factory+output+falls+for+first+time+since+June+2020+as+supply+conditions+worsen+%7c+S%26P+Global+ http%3a%2f%2fprod.azure.ihsmarkit.com%2fmarketintelligence%2fen%2fmi%2fresearch-analysis%2fworldwide-factory-output-falls-for-first-time-since-june-2020-as-supply-conditions-worsen-May22.html","enabled":true}]}, {"name":"rtt","enabled":true,"mobdesc":"Top"}

]}