Customer Logins

Obtain the data you need to make the most informed decisions by accessing our extensive portfolio of information, analytics, and expertise. Sign in to the product or service center of your choice.

Customer Logins

ECONOMICS COMMENTARY

Sep 10, 2021

Hints of stagflation cause fresh headaches for central banks

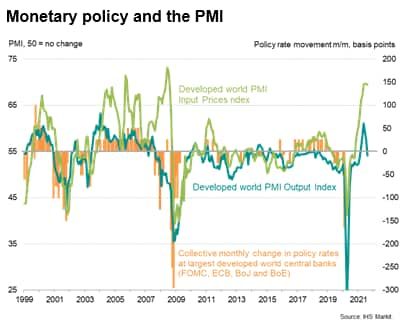

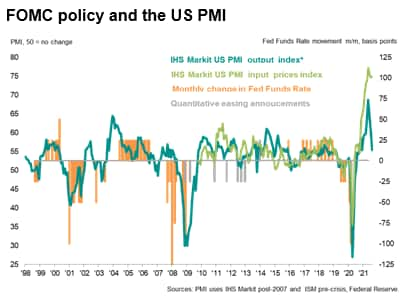

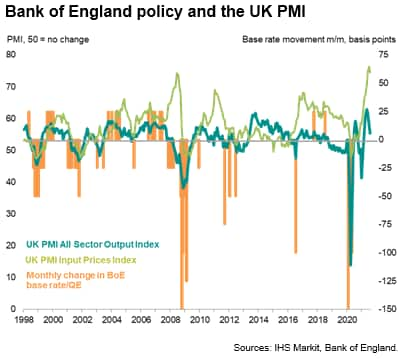

Recent PMI data have sent diverging signals on the path of central bank policy tapering. The latest data can be typified by stagflation, with growth slowing sharply while price pressures remain elevated. There are different signals for different economies, however, and also possibly some parallels from the global financial crisis, which hint at the Bank of England and FOMC potentially pulling back on tapering pandemic-related stimulus.

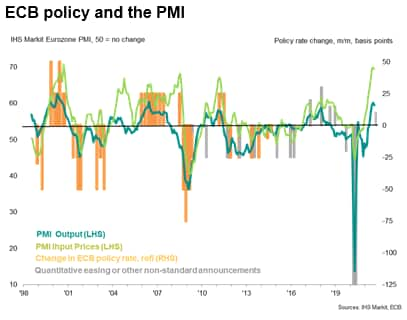

ECB takes the lead in 'taper' action

There's been plenty of talk of tapering in recent months but first actual action among the world's major developed economy central banks was seen at September's policy meeting of the European Central Bank's Governing Council, which saw a reduction in the rate of bond buying in the bank's Pandemic Emergency Purchase Programme (PEPP).

While this merely represents a tweaking, or recalibrating, of the rate of bond buying, it is still widely seen as a step towards the tapering of policy (though read more about the decision here, where it is noted that the ECB deliberately avoided any reference to 'tapering' and that it is important to stress that net PEPP purchases are just one facet of what will remain a highly accommodative monetary policy stance).

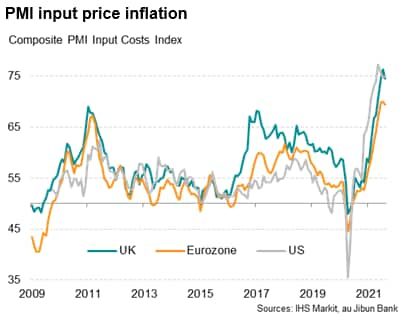

The decision comes in response to a strong economic rebound from the depths of the pandemic, which has been accompanied by rising inflationary pressures. With the IHS Markit Eurozone PMI holding close to a 16-year high again in August, the economy looks set to have regained its pre-pandemic levels by the end of the year; far earlier than many had previously expected. At the same time, the eurozone PMI price indices have been elevated at two-decade highs, with rising costs feeding through to the highest consumer price inflation rate for ten years, at 3.0%.

Eurozone shows greater Delta resilience

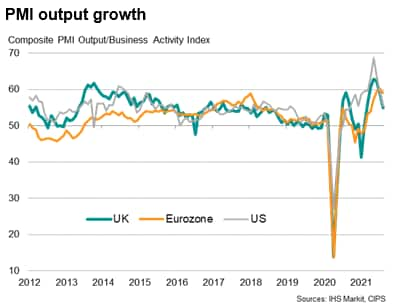

The US Federal Reserve and the Bank of England have meanwhile been even more vocal in raising the possibility of imminent policy tapering, but PMI data for both economies have since disappointed, accompanied by a sharp slowing in US non-farm payroll growth.

The IHS Markit/CIPS Composite PMI for the UK fell from 59.2 in July to 54.8 in August, its lowest since February. The equivalent IHS Markit US PMI meanwhile slumped from 59.9 to 55.4, it lowest so far this year. Both US and UK PMIs are therefore well below the eurozone reading of 59.0 which, while off the recent peak, has shown far greater resilience in the face of the COVID-19 Delta wave.

Price pressures have meanwhile shown few signs of abating to any significant degree in the US or UK despite the economic growth slowdown. In fact, input price inflation in the US and UK is running far higher than in the eurozone, albeit with some slight cooling evident in all cases.

Policy clues sought form upcoming data

Putting historical central bank policy decisions in the context of these PMI output and price data underscores how the recent PMI data give some weight to the ECB's call for some move towards restraining policy stimulus, but the case for tapering in the US and UK is more nuanced, and has arguably been greatly reduced by the recent steep falls in the PMI output indicators.

Much depends on whether these recent falls in the UK and US output indicators prove short lived. A widely-held concern in all economies is that sustained materials price growth, caused by shortages and supply constraints resulting from the pandemic, will lead to higher wage inflation, in turn causing consumer price inflation to remained higher for longer. There is already some evidence that this second-round wage effect is occurring. If the slowdowns in the US and UK are being driven by short-term disruptions from the Delta variant, then output growth could soon recover, reinstating the case for tapering.

However, an opposing concern is that too much emphasis can be placed on price data by central banks, especially in times of economic recovery, when the focus should arguably lie on the output data. It is, after all, rare that price pressures remain elevated for long if demand collapses. In the immediate rebound from the global financial crisis, for example, the ECB responded to rising price pressures with a tightening of policy, contrasting with the more accommodative stances adopted by the FOMC and Bank of England. In that case, the ECB had to swiftly reverse its policy decisions as the recovery faltered, having already been misled into an unwarranted rate hike at the start of the financial crisis due to concerns over prices.

The clear message is that any imminent tapering of monetary policy could exacerbate a Delta-wave slowdown, harming the recoveries and even causing renewed downturns. In such a scenario, it could be argued that the central banks should await further data before starting to adjust policy.

Policy clues sought from upcoming data

The upcoming PMI data will therefore provide important clues as to policy direction. In particular, we will be looking to assess the extent to which slower output growth is being caused by the Delta variant or if demand growth is slowing as rebounds from the pandemic downturns peak. We will also be seeking clues as to whether shortages of materials and staff are continuing to push costs higher, or whether the recent peaking in the PMI price data represents a turning point.

Capacity indicators such as the suppliers' delivery times index and backlogs of work indices in particular, which have signalled unprecedented global capacity constraints in recent months, will be gleaned for additional insights into the extent to which demand is running ahead of supply.

Chris Williamson, Chief Business Economist, IHS Markit

Tel: +44 207 260 2329

chris.williamson@ihsmarkit.com

© 2021, IHS Markit Inc. All rights reserved. Reproduction in whole

or in part without permission is prohibited.

Purchasing Managers' Index™ (PMI™) data are compiled by IHS Markit for more than 40 economies worldwide. The monthly data are derived from surveys of senior executives at private sector companies, and are available only via subscription. The PMI dataset features a headline number, which indicates the overall health of an economy, and sub-indices, which provide insights into other key economic drivers such as GDP, inflation, exports, capacity utilization, employment and inventories. The PMI data are used by financial and corporate professionals to better understand where economies and markets are headed, and to uncover opportunities.

This article was published by S&P Global Market Intelligence and not by S&P Global Ratings, which is a separately managed division of S&P Global.

{"items" : [

{"name":"share","enabled":true,"desc":"<strong>Share</strong>","mobdesc":"Share","options":[ {"name":"facebook","url":"https://www.facebook.com/sharer.php?u=http%3a%2f%2fprod.azure.ihsmarkit.com%2fmarketintelligence%2fen%2fmi%2fresearch-analysis%2fhints-of-stagflation-cause-fresh-headaches-for-central-banks-Sep21.html","enabled":true},{"name":"twitter","url":"https://twitter.com/intent/tweet?url=http%3a%2f%2fprod.azure.ihsmarkit.com%2fmarketintelligence%2fen%2fmi%2fresearch-analysis%2fhints-of-stagflation-cause-fresh-headaches-for-central-banks-Sep21.html&text=Hints+of+stagflation+cause+fresh+headaches+for+central+banks+%7c+S%26P+Global+","enabled":true},{"name":"linkedin","url":"https://www.linkedin.com/sharing/share-offsite/?url=http%3a%2f%2fprod.azure.ihsmarkit.com%2fmarketintelligence%2fen%2fmi%2fresearch-analysis%2fhints-of-stagflation-cause-fresh-headaches-for-central-banks-Sep21.html","enabled":true},{"name":"email","url":"?subject=Hints of stagflation cause fresh headaches for central banks | S&P Global &body=http%3a%2f%2fprod.azure.ihsmarkit.com%2fmarketintelligence%2fen%2fmi%2fresearch-analysis%2fhints-of-stagflation-cause-fresh-headaches-for-central-banks-Sep21.html","enabled":true},{"name":"whatsapp","url":"https://api.whatsapp.com/send?text=Hints+of+stagflation+cause+fresh+headaches+for+central+banks+%7c+S%26P+Global+ http%3a%2f%2fprod.azure.ihsmarkit.com%2fmarketintelligence%2fen%2fmi%2fresearch-analysis%2fhints-of-stagflation-cause-fresh-headaches-for-central-banks-Sep21.html","enabled":true}]}, {"name":"rtt","enabled":true,"mobdesc":"Top"}

]}