Customer Logins

Obtain the data you need to make the most informed decisions by accessing our extensive portfolio of information, analytics, and expertise. Sign in to the product or service center of your choice.

Customer Logins

ECONOMICS COMMENTARY

May 05, 2020

Global Manufacturing PMI at 11-year low in April as only China reports growth

- Global manufacturing PMI at lowest since April 2009 amid COVID-19 pandemic

- Especially steep falls in output and new orders

- Record supply shortages reported

- China reported modest output growth with worsening pictures seen in all other countries

- Record rates of decline recorded in 26 of the 32 countries surveyed

- Weak demand likely to subdue recoveries

Global manufacturing collapsed at a rate not seen since the height of the global financial crisis in April as increasingly widespread measures taken to fight the COVID-19 pandemic led to factory closures, slumping demand and supply chain delays.

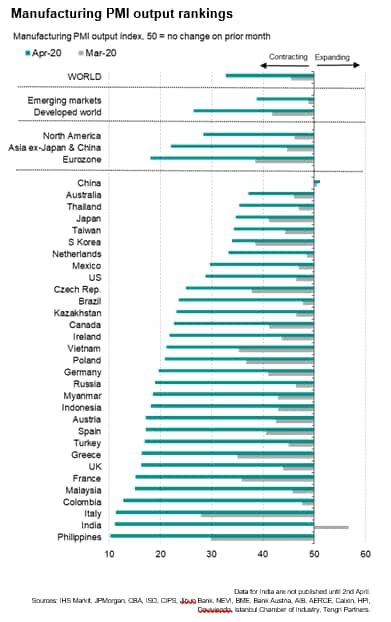

By country, only China saw any output growth, and even here the rise was muted due to falling demand, notably for exports. All other countries saw output trends deteriorate, with record rates of decline recorded in 26 of the 32 countries surveyed by IHS Markit. Excluding China, global output consequently fell to an extent exceeding that seen even during 2009.

PMI at 11-year low

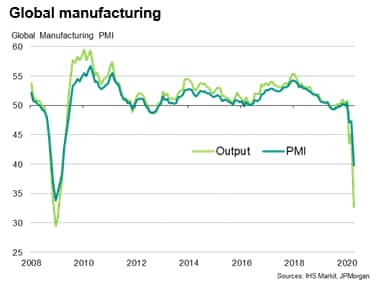

The JPMorgan Global Manufacturing PMI, compiled by IHS Markit from its business surveys in over 30 countries, slumped from 47.3 in March to 39.7 in April, its lowest since the height of the global financial crisis in March 2009. The PMI has signalled three successive months of deteriorating health of worldwide manufacturing, with April seeing a marked intensification of the decline amid the escalating COVID-19 pandemic.

Record supply shock

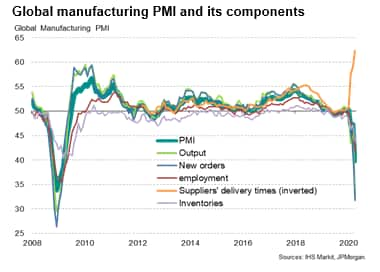

In fact, the headline PMI understated the deterioration in the health of the manufacturing sector in terms of production and demand, as the headline calculation includes suppliers' delivery times as one of its five constituents. As our chart below shows, the suppliers' delivery times index was the only one of the five components to boost the PMI, indicating the most substantial lengthening of delivery times ever recorded in the survey's 22-year history.

Suppliers' delivery times usually move in the same cycle as the other PMI components. In times of strong economic growth, more inputs are demanded by manufacturers to support higher production, putting pressure on suppliers whose lead-times then lengthen.

Conversely, at times of slumping demand, manufacturers buy fewer inputs meaning suppliers have more stock with which to service customers, and lead-times consequently tend to shorten. Such a scenario was clearly evident during the slump in demand seen during the global financial crisis.

However, the current situation is unusual, because demand has slumped but enforced factory closures due to the COVID-19 outbreak mean supplies of inputs are in short supply.

Rather than surging demand causing supply delays, we are seeing a supply shock. This shock has artificially boosted the PMI through the lengthening of lead-times. In reality, the supply shock has constrained production in many companies.

Focus on output and new orders indices

To get a better picture of the impact of COVID-19 on recent production and demand, we need to focus on the survey's output and new orders indices. Both fell to greater extents than the headline PMI, dropping 12.4 and 11.7 index points respectively during April compared with the 7.6 point drop in the PMI.

The declines pushed both the global output and new orders indices down to their lowest since January 2009. The survey's output index is historically consistent with global production falling at an annual rate in excess of 15%, though experience from the global financial crisis suggest that the actual decline could even be somewhat steeper than that indicated by the survey index.

The slump in orders books has been in part a consequence of worldwide trade drying up amid the COVID-19 lockdowns. New export orders placed at manufacturers fell globally to a degree exceeding that seen even during the global financial crisis in April, indicative of global trade collapsing at an annualised rate of approximately 50% ( see our research note on global trade here).

China stabilises, but rest of world sees biggest production fall since 2009

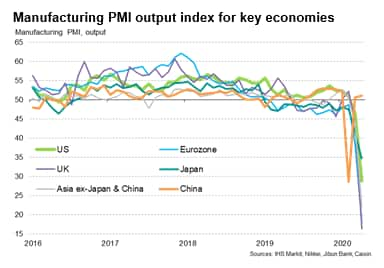

The latest survey data were collected between 7th and 24th April, a time when China continued to ease some of its restrictions on travel and company closures but most other parts of the world, notably Europe and the US, remained in lockdowns that had commenced in the second half of March. Consequently, of the 32 countries for which PMI data were collected, only China reported a PMI output index in excess of 50, signalling a month-on-month increase in production.

However, even the increase in China remained worryingly subdued, with both March and April having seen only very modest gains after a record decline in February. Weak production was linked to a further fall in new order inflows during April.

All other countries saw output fall at faster rates than March (though in the case of India, production fell after having risen in March reflecting a later lockdown than other countries).

The steepest decline was reported in the Philippines followed by India and then Italy.

Survey record rates of production decline were seen in all European countries, as well as in Turkey, Russia and Kazakhstan.

In the Americas, record falls were seen in Canada, Mexico, Brazil and Colombia, while in the US the decline was the steepest since 2009.

In Asia Pacific, survey output indices hit record lows in India, Indonesia, Vietnam, Malaysia, Thailand, Myanmar, the Philippines and Australia, but remained off prior GFC lows in Japan, South Korea and Taiwan.

Will production rebound?

Looking further ahead, it is reasonable to expect a rebound in manufacturing, but questions remain as to how durable this rebound will be.

In the first instance, supply constraints should ease (notably from China) when more factories come back online from virus-related shutdowns, all of which will help boost production in the short term. In fact, judging by government announcements, it seems likely that April may prove to be the low-point for the initial impact from the pandemic on manufacturing, suggesting business conditions should start to improve from henceforth.

However, the concern is that global demand for manufacturers will remain well below that seen prior to the pandemic for some time. Both businesses and consumers are likely to remain cautious in relation to spending as uncertainty persists and unemployment spikes higher. There is therefore a strong possibility of growth fading again after an initial rebound.

Caution in reading survey indices

Finally, as we look ahead to what the surveys may indicate for recoveries, it's worth keeping in mind that a PMI reading of 50 merely means no change on the prior month. Given the recent experience of China, we can expect many of the world's PMIs to move closer to 50 in the coming months. This may look v-shaped on a chart, but don't be misled.

A reading of 50 will in fact mean none of the lost output has been recouped. The PMI would need to rise commensurately higher than 50 to make up for an equivalent drop below 50 in the prior month. Index readings of 60, 70 and even 80 are needed to signal meaningful recoveries from the extensive declines seen recently and, given the glacial pace at which COVID-19 restrictions are likely to be eased, such readings cannot be reasonably expected any time soon.

For more information contact economics@ihsmarkit.com.

Chris Williamson, Chief Business Economist, IHS

Markit

Tel: +44 207 260 2329

chris.williamson@ihsmarkit.com

© 2020, IHS Markit Inc. All rights reserved. Reproduction in whole

or in part without permission is prohibited.

Purchasing Managers' Index™ (PMI™) data are compiled by IHS Markit for more than 40 economies worldwide. The monthly data are derived from surveys of senior executives at private sector companies, and are available only via subscription. The PMI dataset features a headline number, which indicates the overall health of an economy, and sub-indices, which provide insights into other key economic drivers such as GDP, inflation, exports, capacity utilization, employment and inventories. The PMI data are used by financial and corporate professionals to better understand where economies and markets are headed, and to uncover opportunities.

This article was published by S&P Global Market Intelligence and not by S&P Global Ratings, which is a separately managed division of S&P Global.

{"items" : [

{"name":"share","enabled":true,"desc":"<strong>Share</strong>","mobdesc":"Share","options":[ {"name":"facebook","url":"https://www.facebook.com/sharer.php?u=http%3a%2f%2fprod.azure.ihsmarkit.com%2fmarketintelligence%2fen%2fmi%2fresearch-analysis%2fglobal-manufacturing-pmi-at-11year-low-in-april-as-only-china-reports-growth-may2020.html","enabled":true},{"name":"twitter","url":"https://twitter.com/intent/tweet?url=http%3a%2f%2fprod.azure.ihsmarkit.com%2fmarketintelligence%2fen%2fmi%2fresearch-analysis%2fglobal-manufacturing-pmi-at-11year-low-in-april-as-only-china-reports-growth-may2020.html&text=Global+Manufacturing+PMI+at+11-year+low+in+April+as+only+China+reports+growth+%7c+S%26P+Global+","enabled":true},{"name":"linkedin","url":"https://www.linkedin.com/sharing/share-offsite/?url=http%3a%2f%2fprod.azure.ihsmarkit.com%2fmarketintelligence%2fen%2fmi%2fresearch-analysis%2fglobal-manufacturing-pmi-at-11year-low-in-april-as-only-china-reports-growth-may2020.html","enabled":true},{"name":"email","url":"?subject=Global Manufacturing PMI at 11-year low in April as only China reports growth | S&P Global &body=http%3a%2f%2fprod.azure.ihsmarkit.com%2fmarketintelligence%2fen%2fmi%2fresearch-analysis%2fglobal-manufacturing-pmi-at-11year-low-in-april-as-only-china-reports-growth-may2020.html","enabled":true},{"name":"whatsapp","url":"https://api.whatsapp.com/send?text=Global+Manufacturing+PMI+at+11-year+low+in+April+as+only+China+reports+growth+%7c+S%26P+Global+ http%3a%2f%2fprod.azure.ihsmarkit.com%2fmarketintelligence%2fen%2fmi%2fresearch-analysis%2fglobal-manufacturing-pmi-at-11year-low-in-april-as-only-china-reports-growth-may2020.html","enabled":true}]}, {"name":"rtt","enabled":true,"mobdesc":"Top"}

]}