Customer Logins

Obtain the data you need to make the most informed decisions by accessing our extensive portfolio of information, analytics, and expertise. Sign in to the product or service center of your choice.

Customer Logins

ECONOMICS COMMENTARY

Mar 05, 2015

Six years of record low UK interest rates, and few signs of policy tightening soon

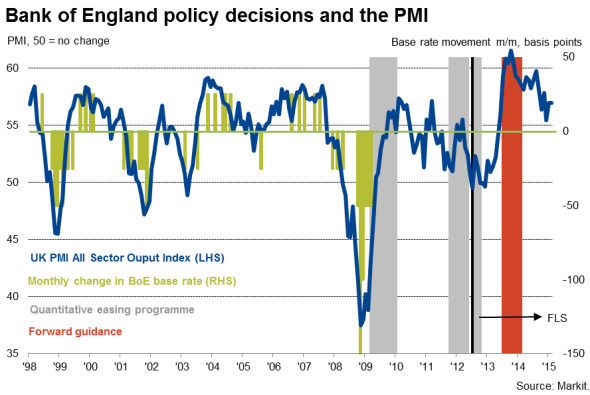

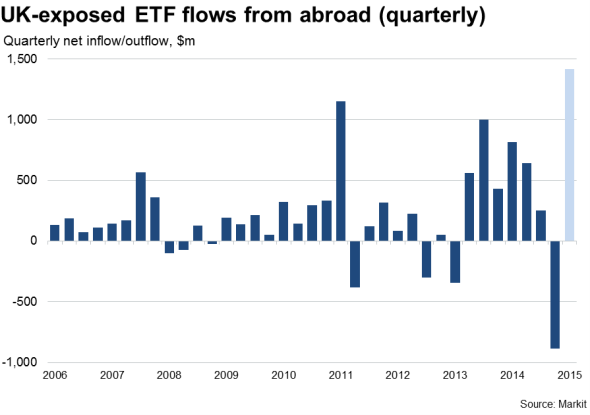

The Bank of England held interest rates at 0.5% at the March meeting of the Monetary Policy Committee, marking the six-year anniversary of record-low interest rates. While the current UK economic performance is perhaps the best we've seen since the financial crisis struck, there are many reasons to believe that any increase in interest rates from this all-time low still looks a long way off. This combination of solid growth and loose policy has lured overseas money into UK-exposed investments at a record rate so far this year.

The case for higher interest rates

The Bank's base rate was slashed to an emergency all-time low of 0.5% in March 2009 as the economy collapsed amid the spiralling global financial crisis. Since then there have been a number of false dawns, but recently the economy is showing real signs of a sustainable and robust recovery. The PMI surveys are signalling economic growth of 0.6% in the first quarter, building on 2.6% growth in 2014. Unemployment has meanwhile plummeted to 5.7%, its lowest since mid-2008. Just two years ago, the jobless rate was 8.0%.

The missing element of this recovery has been a revival of wage growth, but there are signs that pay pressures are continuing to rise steadily. Private sector pay grew at an annual rate of 2.5% in the three months to December, and with the PMI surveys having signalled near-record employment growth in the first two months of 2015, the labour market looks to have continued to tighten so far this year.

Furthermore, although still 48% lower than the highs seen last year, Brent crude is up 33% since the lows reached in mid-January which, alongside rising pay growth and the ongoing economic recovery, suggests we may see inflation start to pick up again, probably in the second half of the year.

The current upturn is therefore in many ways the most promising seen since the financial crisis struck.

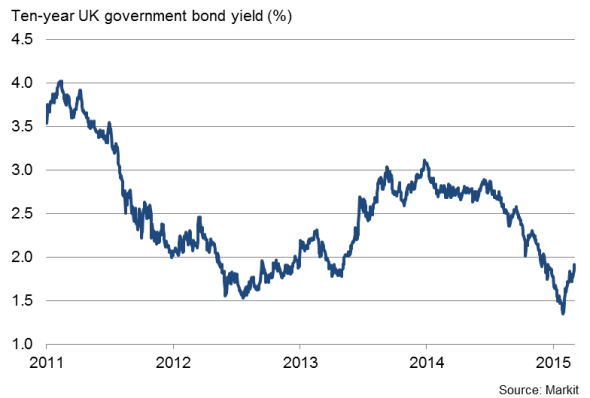

The bond markets are therefore starting to price in the prospect of higher interest rates. Yields on benchmark 10-year gilts are up from a low of 1.35% at the end of January to 1.90%, according to Markit data.

But no rush to tighten policy

However, there are plenty of reasons to believe that any increase in interest rates still looks a long way off.

First, in the near term, uncertainty about the General Election is likely to not only weaken the pace of economic growth but also deter policymakers from adding further uncertainty about monetary policy.

Second, looking further out, the current upturn is being driven by low inflation, which has meant pay is now rising in real terms and lower utility bills and petrol prices are helping drive up consumer spending on non-fuel items. If inflation were to rise again, there is a concern that this stimulus from lower prices would rapidly fade.

Third, wage growth even at 2.5% remains muted by historical standards, and well below rates that would typically worry policymakers into raising interest rates. Even if private sector pay is showing signs of accelerating, low public sector pay growth is likely to persist for some years to come, keeping overall wage growth below the 4-5% levels that tend to trigger inflation alarm bells.

Fourth, the housing market - the heating-up of which was a key source of concern throughout much of last year - is showing signs of cooling. Homeowners' views on the value of their properties hit a one-and-a-half year low in February.

Fifth, the Bank of England, eager to prevent any further rise in sterling, will inevitably seek to hold off raising rates for as long as feasibly possible, as tighter policy in the UK will contrast with loosing policy at the ECB. Sterling is already at its highest since 2008 on a trade-weighted basis.

Furthermore, although bond yields have risen, with 10-year yields at less than 2%, there is clearly not much rate-hiking action being priced into the markets. Futures markets are also not pricing in the first rate rise until at least mid-2016.

Government borrowing costs

It's perhaps not surprising, therefore, that investors continue to seek exposure to UK markets, attracted by the prospect of ongoing strong economic growth while interest rates look set to remain at record lows for the foreseeable future. Overseas listed funds with an exposure to the UK are on course to see the largest inflows on record in the first quarter, according to Markit's ETF database, albeit reversing steep outflows in the final quarter of last year.

Chris Williamson | Chief Business Economist, IHS Markit

Tel: +44 20 7260 2329

chris.williamson@ihsmarkit.com

{"items" : [

{"name":"share","enabled":true,"desc":"<strong>Share</strong>","mobdesc":"Share","options":[ {"name":"facebook","url":"https://www.facebook.com/sharer.php?u=http%3a%2f%2fprod.azure.ihsmarkit.com%2fmarketintelligence%2fen%2fmi%2fresearch-analysis%2f05032015-economics-six-years-of-record-low-uk-interest-rates-and-few-signs-of-policy-tightening-soon.html","enabled":true},{"name":"twitter","url":"https://twitter.com/intent/tweet?url=http%3a%2f%2fprod.azure.ihsmarkit.com%2fmarketintelligence%2fen%2fmi%2fresearch-analysis%2f05032015-economics-six-years-of-record-low-uk-interest-rates-and-few-signs-of-policy-tightening-soon.html&text=Six+years+of+record+low+UK+interest+rates%2c+and+few+signs+of+policy+tightening+soon","enabled":true},{"name":"linkedin","url":"https://www.linkedin.com/sharing/share-offsite/?url=http%3a%2f%2fprod.azure.ihsmarkit.com%2fmarketintelligence%2fen%2fmi%2fresearch-analysis%2f05032015-economics-six-years-of-record-low-uk-interest-rates-and-few-signs-of-policy-tightening-soon.html","enabled":true},{"name":"email","url":"?subject=Six years of record low UK interest rates, and few signs of policy tightening soon&body=http%3a%2f%2fprod.azure.ihsmarkit.com%2fmarketintelligence%2fen%2fmi%2fresearch-analysis%2f05032015-economics-six-years-of-record-low-uk-interest-rates-and-few-signs-of-policy-tightening-soon.html","enabled":true},{"name":"whatsapp","url":"https://api.whatsapp.com/send?text=Six+years+of+record+low+UK+interest+rates%2c+and+few+signs+of+policy+tightening+soon http%3a%2f%2fprod.azure.ihsmarkit.com%2fmarketintelligence%2fen%2fmi%2fresearch-analysis%2f05032015-economics-six-years-of-record-low-uk-interest-rates-and-few-signs-of-policy-tightening-soon.html","enabled":true}]}, {"name":"rtt","enabled":true,"mobdesc":"Top"}

]}