Customer Logins

Obtain the data you need to make the most informed decisions by accessing our extensive portfolio of information, analytics, and expertise. Sign in to the product or service center of your choice.

Customer Logins

BLOG

Dec 19, 2019

WTO dysfunction

The World Trade Organization's (WTO) Appellate Body on 10 December lost its quorum to hear new appeals after the United States vetoed the appointment of new judges. Reforms to the WTO demanded by the US are unlikely to advance during 2020, likely resulting in the growth of alternative dispute resolution pathways.

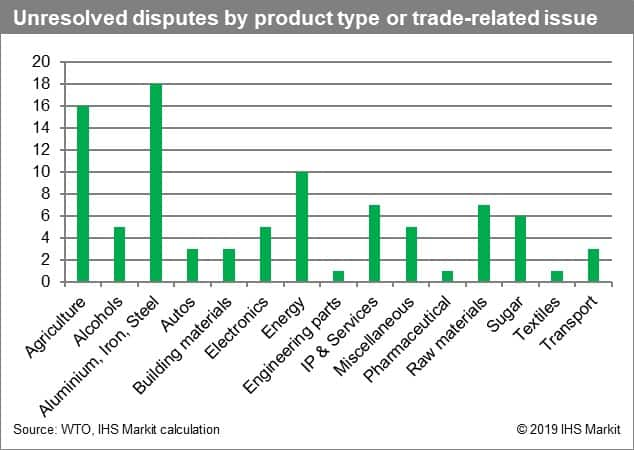

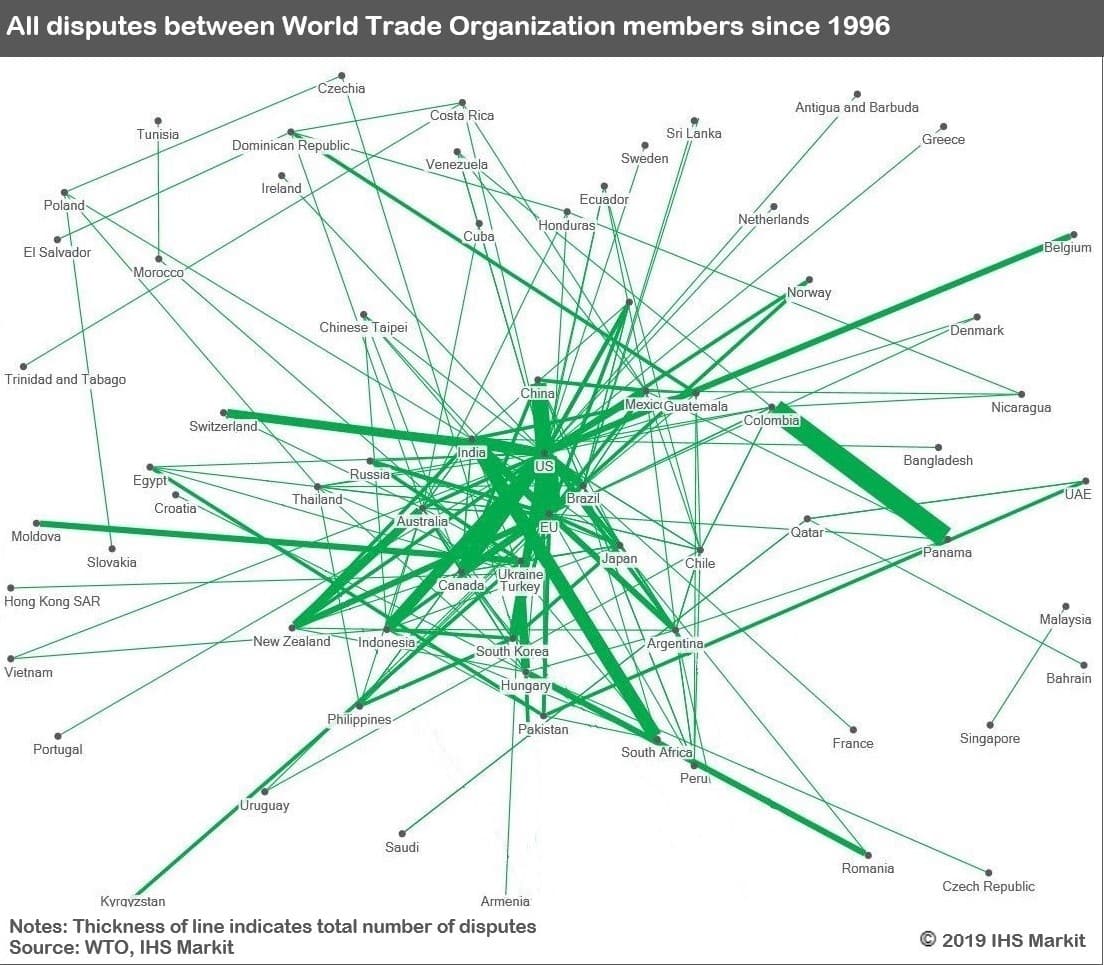

As the World Trade Organization's (WTO) Appellate Body (AB) ceases to function, around 88 trade disputes are very likely to remain unresolved, primarily involving agricultural goods; aluminum, iron, and steel; energy; and raw materials, which are traded by the United States, the European Union, and China. By 2017, the US had overtaken the EU in having the largest number of unresolved complaints against it. Complaints against the US doubled in 2018, as China, the EU, Canada, and other countries submitted 19 complaints against the US's imposition of duties on a range of goods, including aluminum and photovoltaic products. India received the largest number of complaints in 2019, with seven in total, relating to export subsidies on sugar, and duties and tariffs on ICT goods. The US has also filed the largest number of complaints since 1996 (124 in total), primarily targeting China (23) and the EU (21) and is the most frequent respondent (receiving 164 complaints). Without a functioning AB, the case backlog will increase, given that 68% of panel responses since 1996 have been appealed and referred to the AB. The entire dispute process - including appeals - is mandated by the WTO to be completed within 12-18 months, but this has increased to around 24 months on average.

The US is very unlikely to support new appointments to the AB, which require consensus among all WTO members, because of multiple perceived failings that are unlikely to be reformed in 2020. The US has blocked all appointments to the AB since 2016 because of several criticisms (listed as follows), which are very unlikely to be fully addressed by WTO members:

- The AB acts as a routine court of appeal functioning beyond its original mandate as a technical advisory body;

- The appeals process takes too long, resulting in respondents benefiting from an ongoing imbalance in trading relationships;

- The AB relies on precedent in its adjudication of cases, disadvantaging the US. Of the 14 appeals launched by the US only four were upheld, whereas the WTO upheld twice the number of EU appeals;

- 'Developing country' status is adopted unfairly by multiple countries, including China and historically South Korea in protecting their agricultural sector, to gain trade advantages;

- China is treated as a 'market economy' despite heavily subsidizing its state-owned enterprises.

The European Commission wants to expedite appeal decisions in line with the currently mandated 90-day timeframe and incorporate environmental and labor rights considerations into WTO rules; China supports this, but the US is very unlikely to be satisfied. The Commission's proposed amendments to the AB were originally submitted in November 2018 and supported by the Australia, Canada, China, New Zealand, India, and Mexico, but were ultimately not adopted because of US opposition. The Commission believes that the US is not fully committed to reforming the WTO but does want to ensure that China fully complies with WTO rules. China would probably support the Commission's reforms as it seeks to build alliances within the WTO. The US is particularly concerned that the EU does not distinguish between market and non-market economies when calculating dumping margins; instead, using an alternative methodology that the US perceives as benefiting Chinese trade. Fifteen years after its accession to the WTO, China has, however, withdrawn complaints against the EU and the US for not granting it market economy status, indicating some flexibility in supporting new reforms.

China is probably willing to rectify trade distortions and existing government subsidies, depending on the health of its economy during 2020. However, in the absence of deeper reforms to the WTO, China is likely to rely more heavily on arbitration processes established under its Belt and Road Initiative, and by expediting the finalization of free trade agreements (FTA), especially the Korea-Japan-China FTA and the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP) Agreement.

The EU is likely to begin attracting larger economies to an alternative dispute resolution pathway, including by issuing new sanctions or tariffs directly following the dispute settlement body's panel phase. The European Commission on 12 December 2019 proposed an amendment to the EU trade enforcement regulation that would allow the EU to respond if the WTO's AB did not deliver a final ruling in trade disputes, even when this ruling was blocked by another WTO member. In addition, the Commission in June 2019 finalized an alternative dispute resolution mechanism with Canada that operates under existing WTO rules, substituting for the dysfunctional AB.

Trading partners in emerging markets are more likely to resolve trade disputes by agreeing that WTO panel decisions are final, precluding WTO arbitration and appeals to the AB. Indonesia and Vietnam agreed to such a mechanism in March 2019 in a dispute over iron and steel products.

Indicators of changing risk environment

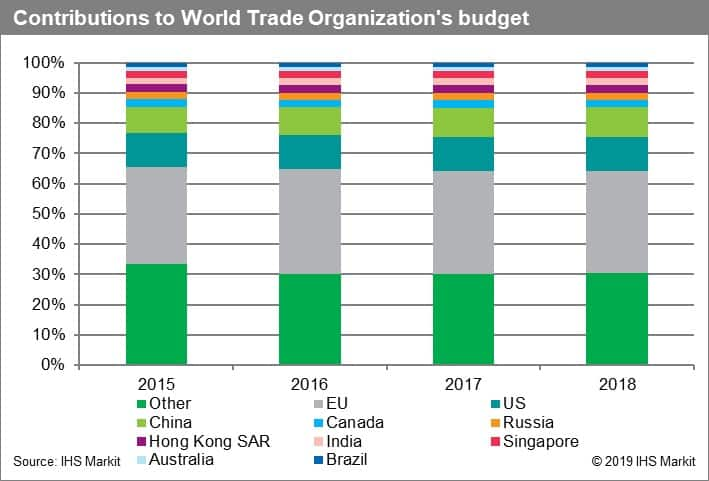

- The US takes the very unlikely step of either withdrawing funding to the WTO or blocking renewal of the WTO's budget on 1 January 2020, probably resulting in dysfunction spreading beyond the AB to the WTO's Secretariat.

- The US, the EU, or other advanced economies such as Canada or Australia reduce their contributions to the WTO, indicating China and India will increase their contributions in response, increasing their influence in rule-setting and dispute resolution.

- In the longer term, China and India support reforms to the WTO's governance structure that increase the voting power of emerging-market economies relative to advanced economies (such as the US and the EU), likely reducing the growth of non-WTO dispute resolution pathways.

- If China joins the Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership (CPTPP), this will likely reduce the WTO's dominance in regulating international trade.

- In the unlikely event of the EU concluding a tariff-only free trade agreement with the US in line with WTO rules (excluding regulations on food safety) during 2020, this will indicate that the EU is more likely to make concessions on US demands for reform.

- A more likely indicator of deeper WTO reforms over the two- to five-year outlook would be the EU and the US taking the currently unlikely step of concluding an agreement on food safety standardization.

- If the EU, in line with European Commission's recommendations, reduces subsidies for agriculture under the EU financial framework for 2021-27 being negotiated during 2020, this will increase the likelihood of similar reforms to the WTO and reduce support within emerging-market economies for non-WTO dispute resolution pathways.

{"items" : [

{"name":"share","enabled":true,"desc":"<strong>Share</strong>","mobdesc":"Share","options":[ {"name":"facebook","url":"https://www.facebook.com/sharer.php?u=http%3a%2f%2fprod.azure.ihsmarkit.com%2fmarketintelligence%2fen%2fmi%2fresearch-analysis%2fwto-dysfunction.html","enabled":true},{"name":"twitter","url":"https://twitter.com/intent/tweet?url=http%3a%2f%2fprod.azure.ihsmarkit.com%2fmarketintelligence%2fen%2fmi%2fresearch-analysis%2fwto-dysfunction.html&text=WTO+dysfunction+%7c+S%26P+Global+","enabled":true},{"name":"linkedin","url":"https://www.linkedin.com/sharing/share-offsite/?url=http%3a%2f%2fprod.azure.ihsmarkit.com%2fmarketintelligence%2fen%2fmi%2fresearch-analysis%2fwto-dysfunction.html","enabled":true},{"name":"email","url":"?subject=WTO dysfunction | S&P Global &body=http%3a%2f%2fprod.azure.ihsmarkit.com%2fmarketintelligence%2fen%2fmi%2fresearch-analysis%2fwto-dysfunction.html","enabled":true},{"name":"whatsapp","url":"https://api.whatsapp.com/send?text=WTO+dysfunction+%7c+S%26P+Global+ http%3a%2f%2fprod.azure.ihsmarkit.com%2fmarketintelligence%2fen%2fmi%2fresearch-analysis%2fwto-dysfunction.html","enabled":true}]}, {"name":"rtt","enabled":true,"mobdesc":"Top"}

]}