Customer Logins

Obtain the data you need to make the most informed decisions by accessing our extensive portfolio of information, analytics, and expertise. Sign in to the product or service center of your choice.

Customer Logins

BLOG

Jul 16, 2019

Why eurozone stubborn low inflation rate is a cause for concern

- Ignoring the usual spring volatility, underlying inflation in the eurozone has remained stuck at around 1%, confounding the ECB's long-standing expectation of a pick-up.

- Growth rates in compensation and unit labour costs have accelerated but this has led to compressed profit margins rather than higher core inflation rates.

- With an eye on Japan's experience, the ECB has been aiming to achieve a large "buffer" to ward off potential deflationary risks during a subsequent downturn.

- Its inability to achieve that objective is a worry, given the maturity of the current economic expansion and an abundance of risks.

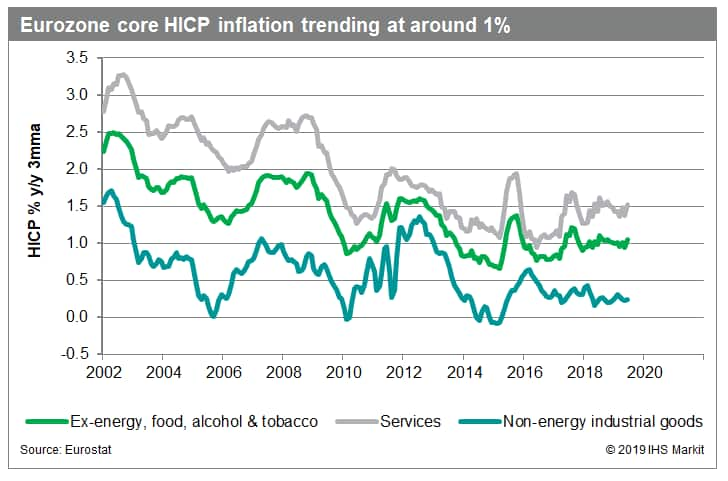

The period from March to June is often characterised by exceptionally high volatility in HICP inflation rates in the eurozone due to seasonal distortions. This year has been no exception. Look through the noise, however, and the core inflation rate has been stuck at around 1% for the best part of two years, continually undershooting the ECB's "below but close to 2%" goal (see first chart).

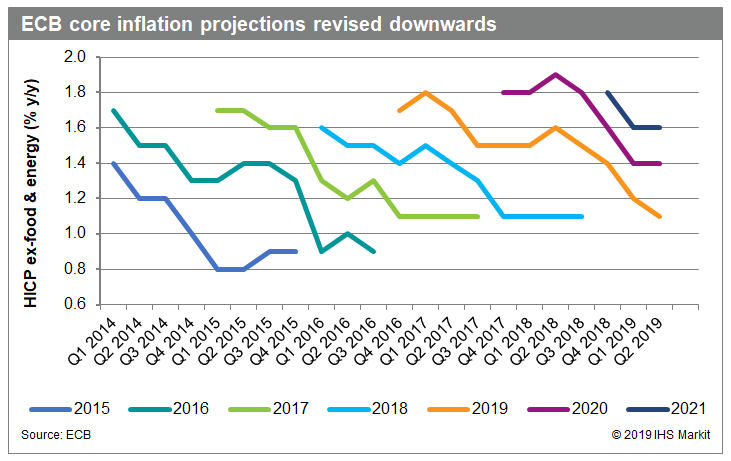

The ECB has been expecting the sharp pick-up in compensation and unit labour cost growth rates (both have been increasing by over 2% y/y in the past few quarters) to filter through to higher core inflation. But this has not been happening and the pattern of ECB forecasts of core inflation having to be repeatedly revised downwards has continued (see second chart).

The ECB initially ascribed the lack of pass-through to lags but as the acceleration in unit labour cost growth has been evident since late 2017, it is clearly more than that. The squeeze on profit margins has proven very persistent and while firms would like to rebuild their margins, they are reluctant to do so in the current sluggish economic environment for fear of losing market share. We have assumed in our baseline forecast a modest and gradual pass-through from prior gains in labour costs into core inflation during 2020 and 2021. But the risks increasingly look skewed to the downside.

In the period after the eurozone crisis, from 2013 to 2016, the ECB was rightly anxious about the threat of a debt-deflation trap emerging. Those concerns faded as the stream of policy stimulus boosted economic growth and the output gap narrowed. But the inflationary "buffer" which the ECB was hoping to generate ahead of a subsequent downturn has proved elusive.

A reprise of the ECB's analysis on this issue in the post-crisis years highlights multiple concerns associated with low inflation. One is that it complicates relative price adjustments between eurozone member states. In other words, in the absence of higher inflation rates in the hitherto more competitive countries (e.g. Germany), those seeking to improve their relative competitiveness are more susceptible to deflation, which could worsen already onerous debt burdens in many of them (e.g. Italy).

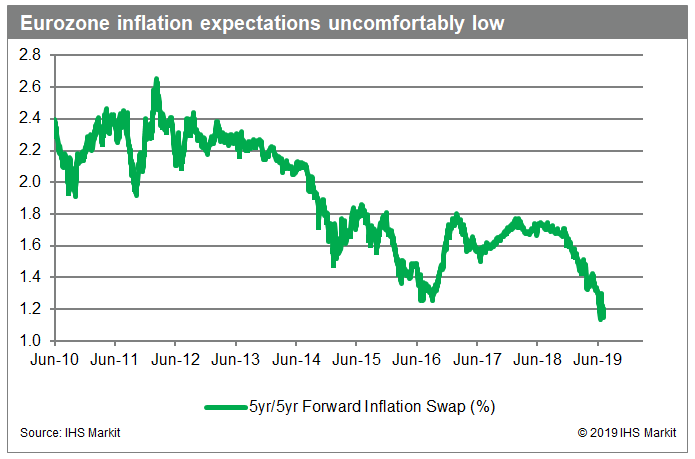

Another issue is the need to anchor expectations to make sure that temporary movements in inflation do not feed into wages and prices and hence become permanent. This has looked increasingly worrisome recently (see third chart). As inflation expectations fall, real interest rates rise and given the limits to how far nominal short-term rates can be lowered, monetary conditions could end up tightening.

Parallels were also drawn with the post-bubble Japanese experience: i.e. successively lower peaks in core inflation during each expansion, followed by a series of downturns which eventually tipped the economy into deflation. A key ECB objective, therefore, was to build a sufficient "buffer" to avoid such an outcome.

Arguments against a Japan-like scenario occurring in the eurozone include the continued ability of policy makers, when working in concert, to reflate the economy, plus the historical downward rigidity of wages and prices in Europe. But how convincing are those arguments currently?

Regarding the former issue, the ECB has already signalled that the door is open to additional QE and a lower deposit facility rate. We expect both to be announced in Q3. But as we outlined in our recent Special Report, the impact of additional monetary policy easing will be limited. Other policy levers, including fiscal stimulus, will need to be used much more effectively and we have doubts about the efficacy of the policy framework in the eurozone. Regarding the latter issue, historically there have been rigidities in wage and price setting. But that may not apply to the same extent post-crisis given the various supply side reforms which have been introduced.

In our baseline scenario, we do not expect a severe shock to push the eurozone into a downward spiral. We expect low but relatively stable growth and inflation rates in the coming years. However, we are cognisant of alternative scenarios, particularly lower probability-higher impact type outcomes. The absence of an inflation "buffer" in the eurozone so late in the cycle is a cause for concern in that respect.

{"items" : [

{"name":"share","enabled":true,"desc":"<strong>Share</strong>","mobdesc":"Share","options":[ {"name":"facebook","url":"https://www.facebook.com/sharer.php?u=http%3a%2f%2fprod.azure.ihsmarkit.com%2fmarketintelligence%2fen%2fmi%2fresearch-analysis%2fwhy-eurozone-stubborn-low-inflation-rate-cause-concern.html","enabled":true},{"name":"twitter","url":"https://twitter.com/intent/tweet?url=http%3a%2f%2fprod.azure.ihsmarkit.com%2fmarketintelligence%2fen%2fmi%2fresearch-analysis%2fwhy-eurozone-stubborn-low-inflation-rate-cause-concern.html&text=Why+eurozone+stubborn+low+inflation+rate+is+a+cause+for+concern+%7c+S%26P+Global+","enabled":true},{"name":"linkedin","url":"https://www.linkedin.com/sharing/share-offsite/?url=http%3a%2f%2fprod.azure.ihsmarkit.com%2fmarketintelligence%2fen%2fmi%2fresearch-analysis%2fwhy-eurozone-stubborn-low-inflation-rate-cause-concern.html","enabled":true},{"name":"email","url":"?subject=Why eurozone stubborn low inflation rate is a cause for concern | S&P Global &body=http%3a%2f%2fprod.azure.ihsmarkit.com%2fmarketintelligence%2fen%2fmi%2fresearch-analysis%2fwhy-eurozone-stubborn-low-inflation-rate-cause-concern.html","enabled":true},{"name":"whatsapp","url":"https://api.whatsapp.com/send?text=Why+eurozone+stubborn+low+inflation+rate+is+a+cause+for+concern+%7c+S%26P+Global+ http%3a%2f%2fprod.azure.ihsmarkit.com%2fmarketintelligence%2fen%2fmi%2fresearch-analysis%2fwhy-eurozone-stubborn-low-inflation-rate-cause-concern.html","enabled":true}]}, {"name":"rtt","enabled":true,"mobdesc":"Top"}

]}