Customer Logins

Obtain the data you need to make the most informed decisions by accessing our extensive portfolio of information, analytics, and expertise. Sign in to the product or service center of your choice.

Customer Logins

BLOG

Jan 10, 2020

Swedish Riksbank defies global monetary policy loosening

- In a widely expected move, the Riksbank hiked the repo rate at the December monetary policy meeting. However, this is not the start of a tightening cycle with the repo rate set to remain unchanged well into 2022.

- The timing and nature of the decision are highly unusual, as most major central banks have been easing policy through 2019, and the Swedish economy is set to grow at the slowest pace in several years. Moreover, the Riksbank continues with its quantitative easing programme until the end of 2020.

- The full reasoning for the "one and done" hike is unclear, but the Riksbank has grown increasingly concerned about the adverse side effects of the negative repo rate.

- The outlook for the Swedish economy remains weak. A negative surprise in 2020 could make the Riksbank push the repo rate back to negative territory.

The Swedish Central Bank (Riksbank) increased its main policy rate (repo rate) by 25 basis points, from -0.25% to 0.00%, in its December meeting. Although the decision was not unanimous, the move had been widely expected. This ends the five-year period when the repo rate was negative (from February 2015 to January 2020), but it is not the start of a tightening cycle. According to the December 2019 monetary policy report, the repo rate is set to remain unchanged well into 2022 (Chart 1), while the Riksbank will continue with its quantitative easing programme until the end of 2020.

The timing for the decision is highly unusual for several reasons. First, Sweden's economy has slowed significantly, with growth in 2019 expected to be the lowest since 2013 (Chart 2), the unemployment rate increasing and inflation below target. It is highly unusual for the central bank to be tightening monetary policy at a time when the economy is hitting the buffers. Second, many central banks, including the Federal Reserve and the European Central Bank, have lowered policy rates in 2019. By tightening rates at a time of global easing, the Riksbank is a notable outlier. Third, the Riksbank is unique among major central banks to have simultaneously hiked rates, while pursuing a quantitative easing programme. Indeed, the Riksbank was keen to emphasize that the overall stance remains expansionary.

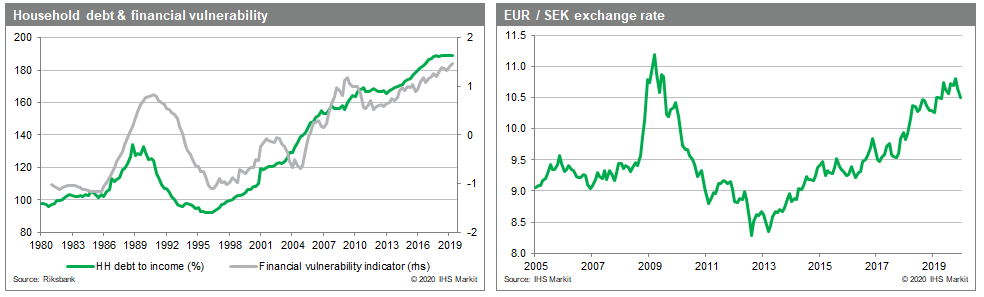

A "one and done" rate hike is highly unusual and the full reasoning for the Riksbank's decision is unclear. However, a key line from the monetary policy report notes that "if negative nominal interest rates are perceived as a more permanent state, the behaviour of economic agents may change and negative effects may arise." The Riksbank has been voicing its concern over the high and increasing level of household indebtedness, which is among the highest in Europe, and the corresponding increase in financial vulnerability (Chart 3).

Other possible reasons, although not explicitly stated, could include the fear that banks will start applying a negative interest rate on retail deposits or concerns over the weakening currency, with the Krona hitting in mid-October the lowest value against the euro since the financial crisis (Chart 4). Importantly, the Riksbank had communicated for months that it plans to exit the negative repo rate around the turn of the year. With growth and inflation largely in line with its earlier forecasts, the Riksbank would face a severe blow to its credibility if it did not carry out what it had promised.

More than anything, the Riksbank was likely driven by an overwhelming desire to exit negative interest rates, due to their adverse side-effects, even if the timing would have been more understandable during the preceding cyclical upswing. The Riksbank has been a pioneer of experimenting with negative rates and this latest decision has implications for the ongoing debate about the merits of negative rates in advanced economies.

Nevertheless, significant downside risks to growth and inflation may force the Riksbank to act again. Regarding the former, high-frequency indicators point to a significant deterioration in economic activity historically consistent with flat or negative growth. Regarding the latter, a stronger krona, following a rally since mid-October, will be disinflationary and may prevent inflation hitting the Riksbank's objective in the coming months. In our baseline for 2020, we expect GDP growth of 1.0%, inflation to average 1.6% and the next rate hike to be in 2022. However, should there be negative surprises in 2020 that would materially affect the outlook, a rate cut back to negative territory would be back on the cards.

{"items" : [

{"name":"share","enabled":true,"desc":"<strong>Share</strong>","mobdesc":"Share","options":[ {"name":"facebook","url":"https://www.facebook.com/sharer.php?u=http%3a%2f%2fprod.azure.ihsmarkit.com%2fmarketintelligence%2fen%2fmi%2fresearch-analysis%2fswedish-riksbank-defies-global-monetary-policy-loosening.html","enabled":true},{"name":"twitter","url":"https://twitter.com/intent/tweet?url=http%3a%2f%2fprod.azure.ihsmarkit.com%2fmarketintelligence%2fen%2fmi%2fresearch-analysis%2fswedish-riksbank-defies-global-monetary-policy-loosening.html&text=Swedish+Riksbank+defies+global+monetary+policy+loosening+%7c+S%26P+Global+","enabled":true},{"name":"linkedin","url":"https://www.linkedin.com/sharing/share-offsite/?url=http%3a%2f%2fprod.azure.ihsmarkit.com%2fmarketintelligence%2fen%2fmi%2fresearch-analysis%2fswedish-riksbank-defies-global-monetary-policy-loosening.html","enabled":true},{"name":"email","url":"?subject=Swedish Riksbank defies global monetary policy loosening | S&P Global &body=http%3a%2f%2fprod.azure.ihsmarkit.com%2fmarketintelligence%2fen%2fmi%2fresearch-analysis%2fswedish-riksbank-defies-global-monetary-policy-loosening.html","enabled":true},{"name":"whatsapp","url":"https://api.whatsapp.com/send?text=Swedish+Riksbank+defies+global+monetary+policy+loosening+%7c+S%26P+Global+ http%3a%2f%2fprod.azure.ihsmarkit.com%2fmarketintelligence%2fen%2fmi%2fresearch-analysis%2fswedish-riksbank-defies-global-monetary-policy-loosening.html","enabled":true}]}, {"name":"rtt","enabled":true,"mobdesc":"Top"}

]}