Customer Logins

Obtain the data you need to make the most informed decisions by accessing our extensive portfolio of information, analytics, and expertise. Sign in to the product or service center of your choice.

Customer Logins

BLOG

Nov 07, 2018

India banking sector risk

On 31 October 2018, The Economic Times reported that the Indian government had invoked Section 7 of the Reserve Bank of India Act, indicating potential direct government interference with central bank policy.

- Political considerations ahead of the upcoming 2019 parliamentary elections are likely the main driver of potential government interference with Reserve Bank of India (RBI) policy, seeking to create a more favorable image of economic policy achievements with the electorate.

- Instability within the RBI and/or a more expansionary monetary policy would increase India's vulnerability to capital outflows and emerging-market risk contagion, encouraging further rupee depreciation, while hurting growth.

- Dilution of the Prompt Corrective Action framework would negatively affect India's banking sector, worsening credit quality and increasing impairment levels.

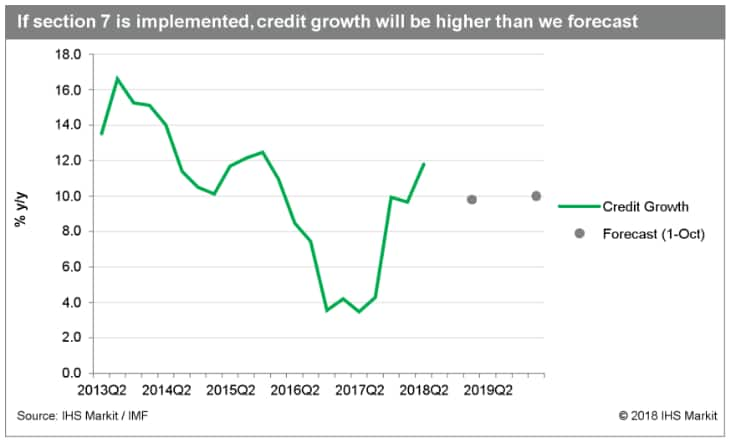

- Even if an easing in RBI policies boosts credit growth temporarily, greater financial volatility and undermined business confidence would lead to a slowdown in private consumption and investment, resulting in additional downgrades to our baseline near-term GDP growth forecast.

Invoking Section 7 would allow the government to issue directives to the Reserve Bank of India (RBI), the central bank, in matters considered to be of public interest. Although neither the government nor the RBI have confirmed The Economic Times' report, the Ministry of Finance issued a statement soon after saying it respected RBI autonomy.

Differences between the government and the RBI have increased in the past year, on issues including the policy direction for non-banking financial companies (NBFCs) and public-sector banks, interest-rate setting, and implementation of the Insolvency and Bankruptcy Code (IBC). On 26 October 2018, the deputy governor of the RBI, Viral Acharya, delivered a speech saying that governments failing to respect the independence of the central bank would incur the "wrath of financial markets".

IHS Markit assesses that - irrespective of government confirmation of invoking Section 7 or otherwise - further public escalation of the rift over policy direction is unlikely, but significant differences will lead to prolonged negotiations, with the government looking to consolidate its position ahead of parliamentary elections in the first quarter of 2019, while the RBI tries to ensure economic and financial stability and consolidation.

Government likely to seek revision of Prompt Corrective

Action framework

The RBI introduced the Prompt Corrective Action (PCA) framework in

the second quarter of 2017 covering 11 public-sector banks and one

private-sector entity. The PCA limits the banks' expansion plans,

seeking to improve their profitability, asset quality and capital

buffers, and overall banking-sector resilience. The PCA initiative

followed the 2016 Asset Quality Review (AQR), which led,

unsurprisingly, to deterioration in reported asset quality,

particularly for public-sector banks. Public-sector banks'

inability to expand credit under the PCA left room for NBFCs to

expand their market share and increase lending. Given the more

relaxed regulatory standards for NBFCs, it is likely that their

expanded credit provision was granted with fewer checks and less

consideration for its effect on the asset quality of the financial

sector. Simultaneously, banks seeking to improve credit risk were

lending to higher credit-rated NBFCs. Given the squeeze in the

provision of funding to infrastructure projects following the

recent collapse of an NBFC (IL&FS), the government is likely to

seek revision of PCA to allow public-sector banks to resume

lending, to fill potential gaps in funding high-profile

infrastructure development in the lead-up to the elections (see

India: 9 October 2018: Indian government's takeover of IL&FS

highlights liquidity risks in financial sector, increases

likelihood of infrastructure contract reviews).

Diversion of RBI reserves to support government budget

is unlikely

Another area of difference between the government and the RBI has

been the level of dividends paid by RBI to the government. Given

growing fiscal pressure from rising global oil prices and increased

public spending ahead of the election, the government is keen to

use what it believes to be RBI's "surplus reserves" to reduce the

fiscal deficit. For the fiscal year ending March 2019, it set a

fiscal deficit target of 3.3% (excluding provincial deficits),

versus 3.5% in fiscal year 2017. The RBI views its holdings of

approximately USD400 billion in foreign-exchange reserves as an

important tool to manage exchange rate risks, and is unlikely to

use such funds for budget support even given government

pressure.

Outlook and implications

Although the RBI-led clean-up of India's banking sector offers

longer-term benefits, growing anti-incumbent political sentiment is

likely to increase the pressure on the government to seek improved

economic performance - or at the very least to stem possible

deterioration - ahead of the upcoming elections. Policy measures to

meet these objectives could include the government pushing to use

RBI reserves to meet its fiscal deficit target, and separately, to

encourage a resumption in state bank lending - particularly for

infrastructure - to avoid high-profile projects stalling prior to

the elections.

IHS Markit assesses that the government and the RBI are likely to follow a consensus-driven approach to address their policy differences, at least publicly; public divergence would increase risk of damaging market sentiment and increasing volatility. Uncertainty over RBI independence is likely to erode investor confidence in the immediate outlook. Recent global emerging-market risk contagion has affected India adversely. The growing pressure on the RBI has the potential to trigger additional capital outflows and could threaten further currency instability. India already has been under increased scrutiny from investors given growing current account and fiscal deficits, with the former adversely affected by sharply rising oil imports (see Global Economics Strategic Report: 25 Sep 2018: Assessment of currency-crisis triggers in emerging markets).

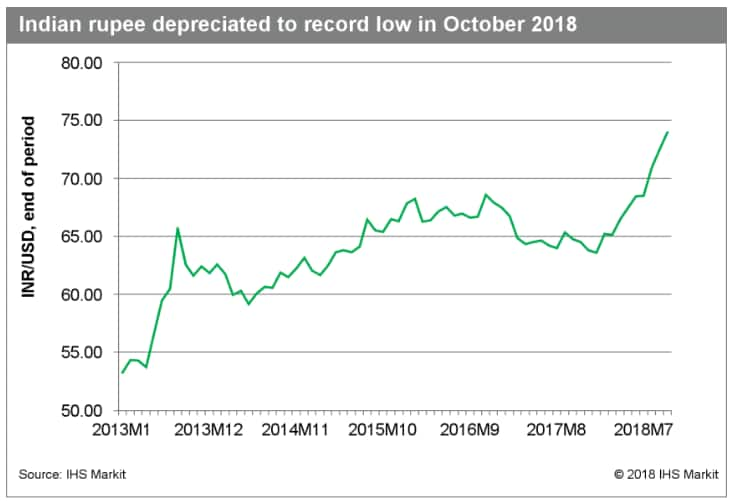

Policy reversals that confirm government interference in central bank policy would indicate the likelihood of renewed adverse pressure on the Indian rupee, which has depreciated sharply in 2018 losing over 15% since end-2017. Conversely, if the government denies invoking Section 7, thereby offering an indication of the RBI's continued autonomy, this is likely to provide some short-term respite for the rupee. However, IHS Markit would not expect any lasting significant improvement, given that external pressures will persist.

Furthermore, dilution or removal of the PCA would indicate longer-run risk deterioration within India's banking sector. Although increased state-directed lending would allay immediate liquidity risks for NBFCs and important infrastructure projects, reduced pressure on state-owned banks to strengthen their financial condition, and encouragement for them instead to lend more before the election is likely to increase future credit risks. In this scenario, bank impairment is likely to increase, with higher credit risk accumulation likely as the PCA had acted as a main deterrent for irresponsible lending. Banks also would have reduced ability to meet Basel III requirements.

The response of RBI Governor Urjit Patel will be crucial to assess the outlook for RBI's autonomy and the extent of government interference. Since The Economic Times' report about Section 7, media reports have suggested Patel will resign in protest. His resignation - and his probable replacement with a governor more compliant with government objectives - would indicate a significantly increased risk of policy adjustments. The RBI has called for a board meeting on 19 November. A subsequent announcement from the RBI indicating it is softening its position on PCA or on budgetary use of RBI reserves would indicate policy reversal with the RBI yielding to government pressures.

Want more on Section 7? Watch our recent webcast

{"items" : [

{"name":"share","enabled":true,"desc":"<strong>Share</strong>","mobdesc":"Share","options":[ {"name":"facebook","url":"https://www.facebook.com/sharer.php?u=http%3a%2f%2fprod.azure.ihsmarkit.com%2fmarketintelligence%2fen%2fmi%2fresearch-analysis%2findia-banking-sector-risk.html","enabled":true},{"name":"twitter","url":"https://twitter.com/intent/tweet?url=http%3a%2f%2fprod.azure.ihsmarkit.com%2fmarketintelligence%2fen%2fmi%2fresearch-analysis%2findia-banking-sector-risk.html&text=India+banking+sector+risk+%7c+S%26P+Global+","enabled":true},{"name":"linkedin","url":"https://www.linkedin.com/sharing/share-offsite/?url=http%3a%2f%2fprod.azure.ihsmarkit.com%2fmarketintelligence%2fen%2fmi%2fresearch-analysis%2findia-banking-sector-risk.html","enabled":true},{"name":"email","url":"?subject=India banking sector risk | S&P Global &body=http%3a%2f%2fprod.azure.ihsmarkit.com%2fmarketintelligence%2fen%2fmi%2fresearch-analysis%2findia-banking-sector-risk.html","enabled":true},{"name":"whatsapp","url":"https://api.whatsapp.com/send?text=India+banking+sector+risk+%7c+S%26P+Global+ http%3a%2f%2fprod.azure.ihsmarkit.com%2fmarketintelligence%2fen%2fmi%2fresearch-analysis%2findia-banking-sector-risk.html","enabled":true}]}, {"name":"rtt","enabled":true,"mobdesc":"Top"}

]}