Customer Logins

Obtain the data you need to make the most informed decisions by accessing our extensive portfolio of information, analytics, and expertise. Sign in to the product or service center of your choice.

Customer Logins

BLOG

Jul 15, 2019

Incorporating country risk for effective investing

Global companies are invested in a diverse variety of markets - increasingly in the developing world. According to UNCTAD, in 2018 58% of FDI went to developing economies. While that year saw a drop of 19% annually into developed economies, developing economies saw an increase of 3% annually. Total FDI into developing economies has increased nearly 50% in the past decade.

However, rapidly developing environments are particularly difficult to predict and are also often less understood by investors coming from the developed world. Companies investing outside their "home base" have to take into account a complex spectrum of country risks. At the extreme end, violent conflict or expropriation can rapidly make an operation less viable and certainly less profitable. Less extreme events can also have a significant impact on investment return - contracts being frustrated by local counterparts, demand contraction and changes in taxation, regulation, currencies and costs. By anticipating potential impacts of this kind, a company can assess if the expected returns on an investment are sufficient to compensate for country risk in locations where there is significant uncertainty.

When evaluating potential investments, companies need to quantify these country risks in financial terms in order to more profitably evaluate, compare, and select investment opportunities. Current tools like sovereign risk indicators reflect only a very limited view of commercially relevant risks and don't account for the significant variability of risks by sector. In fact, these tools often over- or undervalue country risks significantly, by ignoring the on-the-ground realities in exchange for market sentiment.

By looking at the specific risks that impact projects on the ground, we can get a more precise measure of the cash flow impact of risks.

Peru

In Peru, sovereign risk significantly undervalues the risk. Though Peru is not a particularly risky country, there are government stability, terrorism, and protest risks that can have a significant impact on the operating environment in Peru, especially for certain sectors and locations. For example, government stability risks are likely to be high in the next year despite incumbent president Martin Vizcarra on 5 June having survived a congressional vote of confidence over his proposed judicial system and campaign financing reforms. Indeed, if Congress fails to approve these reforms, the president could call again another congressional vote of confidence; if he loses, he can dissolve Congress and call parliamentary elections to break the impasse.

In addition, although incidents of social conflict have declined from a 12-month high of 202 in September 2018, efforts to restart stalled mining developments in Arequipa and Piura, as well as demands of compensation in Apurimac, are likely to provoke anti-mining demonstrations in the next year.

As for terrorism risks, the Sendero Luminoso (SL: Shining Path) insurgent group has declined in strength and scope since its peak in the late 1980s and early 1990s, and no longer poses a security threat beyond the remote coca-growing areas where it operates in the central-southern Valley of the Apurímac, Ene, and Mantaro rivers (VRAEM). However, within the VRAEM, SL poses a significant risk. SL cooperates closely with drug-trafficking groups and its presence in the VRAEM gives rise to ongoing risks of extortion, sabotage, property damage, and kidnapping for firms operating in or around VRAEM. Natural gas, construction firms, and military helicopters face a higher risk of attack within the VRAEM.

Mozambique

Though it is a riskier environment in general, in Mozambique sovereign risk indicators significantly overvalue the risk, particularly with regard to key sectors such as Liquefied Natural Gas (LNG). Mozambique suffered a credit rating downgrade and economic downturn after the International Monetary Fund (IMF) in 2016 discovered USD1.4 billion in 'hidden loans' awarded to state entities. The IMF subsequently suspended assistance and a new program has not yet been forthcoming.

However, the fiscal and regulatory environment for LNG investments has been relatively favorable and predictable for foreign investors, unlike in the case of regional neighbors such as Tanzania, where a political agenda focused on resource nationalism has significantly disrupted finalize of a Host Government Agreement for new LNG projects. In Mozambique, by contrast, Anadarko on 19 June 2019 took a final investment decision for a USD25 billion onshore LNG project, demonstrating the divergence between sovereign and country risk indicators when applied on a sector-by-sector basis.

Quantified results

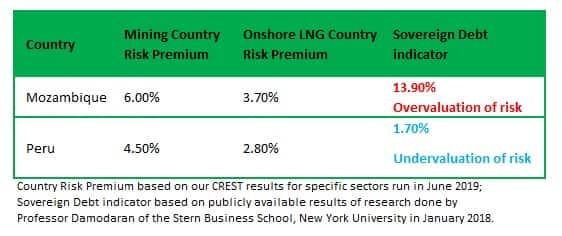

By taking into account the level of risk of these important factors, we find a significant difference in the Country Risk Premium as opposed to the Sovereign Debt indicator, and very different premiums based on the sector. Mozambique, though a riskier operating environment overall, is much less risky than the sovereign debt indicator would suggest; while Peru is a less risky operating environment in general, but riskier in certain sectors such as mining.

By quantifying these on the ground risks, and mapping them to sectors of interest, we can achieve a much more precise measurement of the impact of country risk on project or sector cash flow. This means better investments. Digging into the drivers of that impact make more targeted mitigation possible, to further lower the risk of investment. As all that investment flows to risky markets, this kind of understanding is crucial for having the best strategy.

Learn more about our Country Risk Evaluation & Simulation Tools and how you can use CREST to invest with confidence.

{"items" : [

{"name":"share","enabled":true,"desc":"<strong>Share</strong>","mobdesc":"Share","options":[ {"name":"facebook","url":"https://www.facebook.com/sharer.php?u=http%3a%2f%2fprod.azure.ihsmarkit.com%2fmarketintelligence%2fen%2fmi%2fresearch-analysis%2fincorporating-country-risk-for-effective-investing.html","enabled":true},{"name":"twitter","url":"https://twitter.com/intent/tweet?url=http%3a%2f%2fprod.azure.ihsmarkit.com%2fmarketintelligence%2fen%2fmi%2fresearch-analysis%2fincorporating-country-risk-for-effective-investing.html&text=Incorporating+country+risk+for+effective+investing+%7c+S%26P+Global+","enabled":true},{"name":"linkedin","url":"https://www.linkedin.com/sharing/share-offsite/?url=http%3a%2f%2fprod.azure.ihsmarkit.com%2fmarketintelligence%2fen%2fmi%2fresearch-analysis%2fincorporating-country-risk-for-effective-investing.html","enabled":true},{"name":"email","url":"?subject=Incorporating country risk for effective investing | S&P Global &body=http%3a%2f%2fprod.azure.ihsmarkit.com%2fmarketintelligence%2fen%2fmi%2fresearch-analysis%2fincorporating-country-risk-for-effective-investing.html","enabled":true},{"name":"whatsapp","url":"https://api.whatsapp.com/send?text=Incorporating+country+risk+for+effective+investing+%7c+S%26P+Global+ http%3a%2f%2fprod.azure.ihsmarkit.com%2fmarketintelligence%2fen%2fmi%2fresearch-analysis%2fincorporating-country-risk-for-effective-investing.html","enabled":true}]}, {"name":"rtt","enabled":true,"mobdesc":"Top"}

]}