Customer Logins

Obtain the data you need to make the most informed decisions by accessing our extensive portfolio of information, analytics, and expertise. Sign in to the product or service center of your choice.

Customer Logins

BLOG

Nov 20, 2020

Geopolitics in supply chains: The Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership

Big but slow

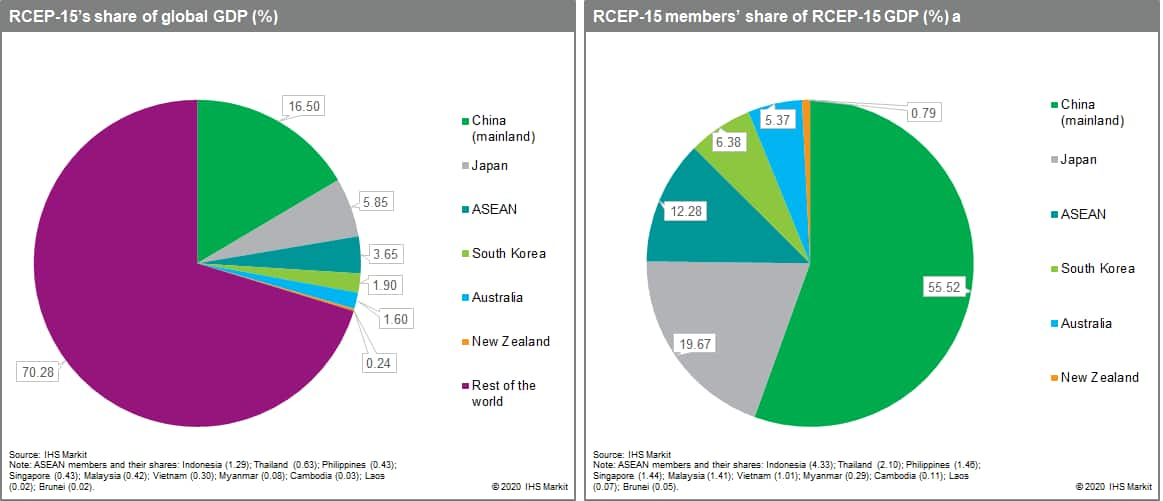

The Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP) will consolidate currently overlapping arrangements between the signatories and unify rules of origin. Negotiations had been underway since 2012 but the supply chain disruption caused by the COVID-19 pandemic gave them new urgency and India's exit from negotiations in late 2019 removed the major obstacle. RCEP provides scope for deeper trade relations in the most economically vibrant region of the world - whose trade is already relatively concentrated in that region. Asian Development Bank estimates suggest about 60% of Asian trade is within Asia, compared with 40% in North America, and similar to the 65% in the EU's single market (based on 2018 IMF data). There are, however, two substantial caveats. First, seven RCEP members are also signatories of the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP), which already seeks tariff elimination on 99% of traded goods (viz, Australia, Brunei, Japan, Malaysia, New Zealand, Singapore, and Vietnam). Second, RCEP's tariff eliminations will be gradually implemented over 20 years, allowing each signatory to adopt it at its own pace. (It first needs to be ratified by nine signatories - most have not indicated a timeline for ratification.) Further, each member country can decide which services sectors are open to competition from other RCEP signatories. - so-called 'positive list members.'

US-China rivalry

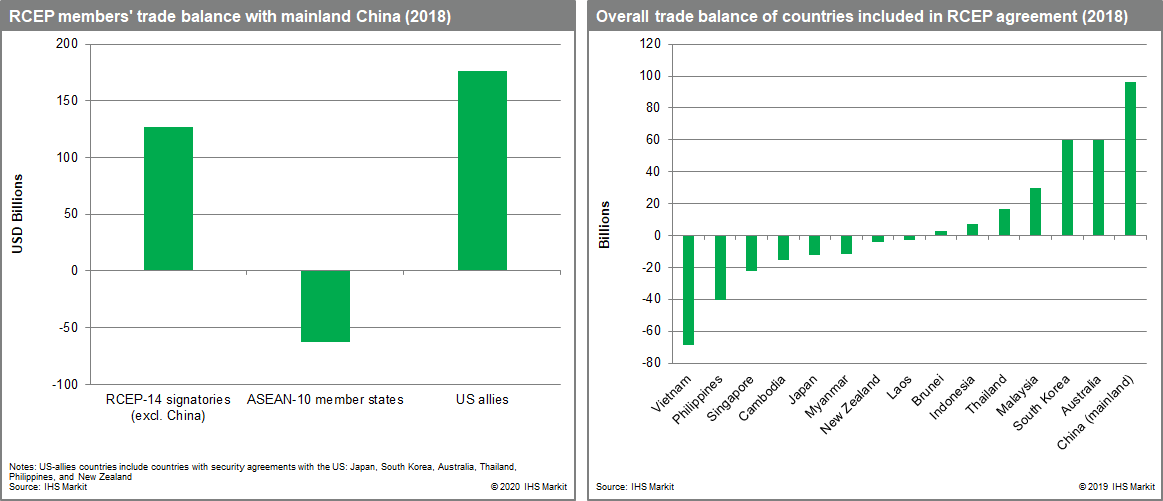

A major difference between RCEP and TPP is that it obviates standards for environmental or labor protections. These were central to the US's ascension to TPP during the Obama administration and give rise to a regulatory tension. If the US under a Biden administration (and/ or to a lesser extent the UK post-Brexit) were to accede to the TPP, at least the seven countries that are part of both RCEP and TPP would face a competitive disadvantage within the RCEP bloc because of the higher environmental and labor standards TPP trade demands. This adds to US incentives to (re)join the TPP in an attempt to curb Mainland Chinese economic influence in Asia, especially the fast-growing economies of ASEAN (where the idea of RCEP originates). It would build on existing relationships. Two-thirds of China's trade with RCEP members is with US-allied countries - diplomatic disputes between these countries and China are likely to have the US-China rivalry in the background and quickly turn into economic disputes. (See forthcoming blog post on Australia-China relations.) Several of these countries also have longstanding territorial disputes with China so periodic political opposition to RCEP - and China's dominant position within it - is likely.

China's Premier Li Keqiang, during an 18 November State Council meeting, highlighted the importance of domestically implementing RCEP-related measures "in accordance with the schedule", likely signaling Chinese commitment to the agreement. RCEP's inclusion of e-commerce, intellectual property, and technological cooperation is likely to favor market access in areas where China has a competitive advantage, including internet platforms, and telecommunication technology - even if many of these sectors are seeing a trend towards higher taxation and protectionism on grounds of national interest. RCEP will also facilitate a proposed trilateral free trade agreement between China (the world's second largest economy), Japan (the third), and South Korea (the tenth), an "RCEP-plus" zone. Japanese and South Korean will be especially competitive in advanced manufacturing sectors, like automotives.

India?

India enjoys a clause in the agreement that gives it the prerogative to accede at a later stage. However, India is unlikely to rejoin, given its USD60 billion trade deficit with China and its demand to reduce tariffs in dairy and e-commerce sectors - both important political constituencies in India. Even guaranteed exemptions from tariff reductions is unlikely to convince the current BJP-led parliament (sitting until 2024). However, Australia and Japan will likely co-operate in future RCEP negotiations to encourage India to rejoin the group, likely to counterbalance China's disproportional economic influence. Australia and Japan probably also assess that India's inclusion into the group will increase the prospect to counterbalance China's regional political influence, given increased bilateral co-ordination via the Supply Chain Resilience Initiative (SCRI).

Even an economic agreement of the potential size of RCEP is likely to be constrained by geopolitical complications.

{"items" : [

{"name":"share","enabled":true,"desc":"<strong>Share</strong>","mobdesc":"Share","options":[ {"name":"facebook","url":"https://www.facebook.com/sharer.php?u=http%3a%2f%2fprod.azure.ihsmarkit.com%2fmarketintelligence%2fen%2fmi%2fresearch-analysis%2fgeopolitics-in-supply-chains-rcep.html","enabled":true},{"name":"twitter","url":"https://twitter.com/intent/tweet?url=http%3a%2f%2fprod.azure.ihsmarkit.com%2fmarketintelligence%2fen%2fmi%2fresearch-analysis%2fgeopolitics-in-supply-chains-rcep.html&text=Geopolitics+in+supply+chains%3a+The+Regional+Comprehensive+Economic+Partnership+%7c+S%26P+Global+","enabled":true},{"name":"linkedin","url":"https://www.linkedin.com/sharing/share-offsite/?url=http%3a%2f%2fprod.azure.ihsmarkit.com%2fmarketintelligence%2fen%2fmi%2fresearch-analysis%2fgeopolitics-in-supply-chains-rcep.html","enabled":true},{"name":"email","url":"?subject=Geopolitics in supply chains: The Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership | S&P Global &body=http%3a%2f%2fprod.azure.ihsmarkit.com%2fmarketintelligence%2fen%2fmi%2fresearch-analysis%2fgeopolitics-in-supply-chains-rcep.html","enabled":true},{"name":"whatsapp","url":"https://api.whatsapp.com/send?text=Geopolitics+in+supply+chains%3a+The+Regional+Comprehensive+Economic+Partnership+%7c+S%26P+Global+ http%3a%2f%2fprod.azure.ihsmarkit.com%2fmarketintelligence%2fen%2fmi%2fresearch-analysis%2fgeopolitics-in-supply-chains-rcep.html","enabled":true}]}, {"name":"rtt","enabled":true,"mobdesc":"Top"}

]}