Customer Logins

Obtain the data you need to make the most informed decisions by accessing our extensive portfolio of information, analytics, and expertise. Sign in to the product or service center of your choice.

Customer Logins

BLOG

Oct 13, 2020

European tourism will lag recovery of other parts of the economy

- The European tourism sector will be a laggard in recovery following the COVID-19 virus crisis due to the sector's vulnerability to re-intensification of infections and the need to have international co-ordination.

- Those countries that can attract visitors from nearby population centres will be quicker to see a recovery of tourism. Alternatively, countries with large domestic populations could offset some of the negative impacts of lost international arrivals.

- Reliance on air travel and/or cruises will delay recoveries, as those industries are likely to be slow in rebounding.

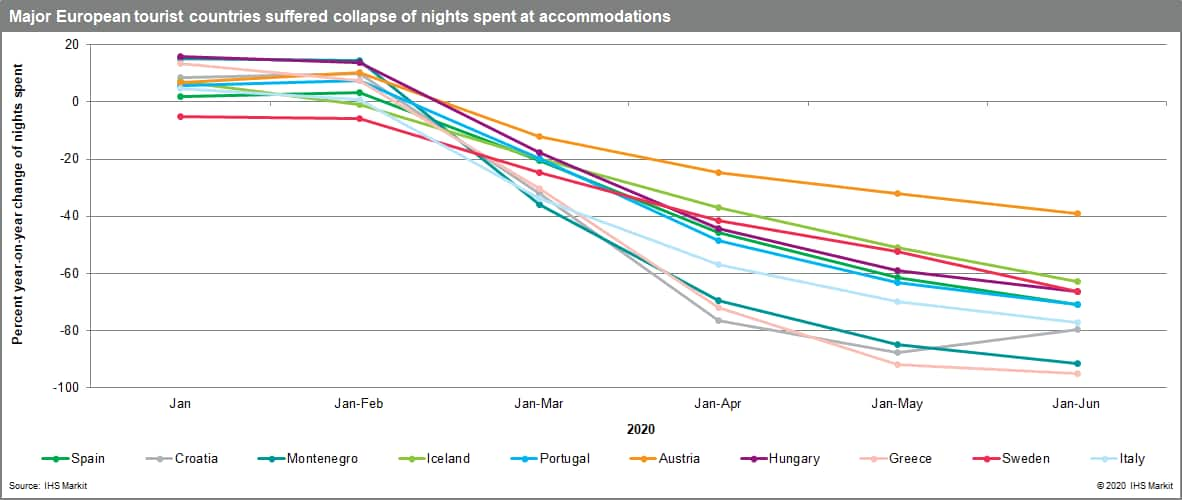

The global spread of the COVID-19 virus has devastated global tourism. The United Nations World Tourism Organization (UNWTO) estimated that total international tourist arrivals plunged by 65% year on year (y/y) in the first half of 2020. Given the weight of the tourism sector for many European countries, overall economic activity will not approach pre-pandemic levels until this sector recovers more substantially.

Returning tourism is dependent not only on domestic policy decisions and limiting the impact of COVID-19 within a country's own borders, but it will require a reliance on foreign countries' policy decisions and elimination or limitation of COVID-19 as well.

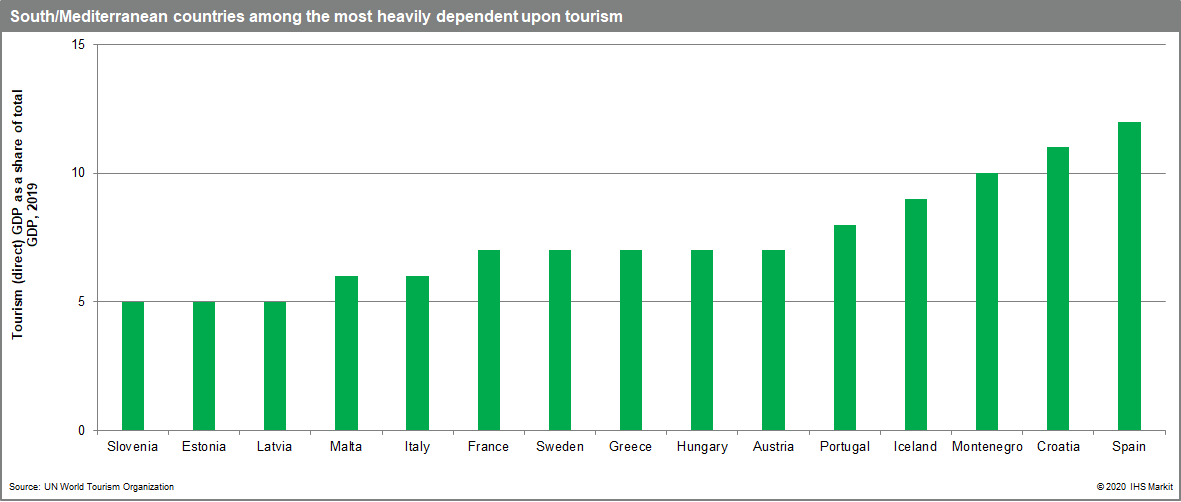

The South/Mediterranean region of Europe is most dependent upon tourism as a share of total GDP. Hopes had been high in May and June that relaxing restrictions, low infection rates, and the release of pent-up demand would provide a boost to third-quarter tourism activity. However, the recovery has not been strong for several reasons.

Containment of COVID-19

The most basic assumption on which the return of tourism depends is that the COVID-19 outbreak has been contained and that visiting a destination is indeed safe. After having initial success in limiting the spread, a resurgence of infections landed Spain back on many countries' travel advisory lists. The Spanish case reflects the risk of introducing large inflows of travellers to a region, even if that region may have succeeded in driving down the pandemic. Fresh inflows of arrivals bring fresh potential transmission vectors, inevitably increasing the risk of a reacceleration of infections.

Travel restrictions

Beyond just the threat of the disease itself, shifting transmission data lead to dramatic changes in travel restrictions and requirements across Europe. Portugal did not arrive on the UK's travel corridor until mid-August, triggering a wave of new visitors. Unfortunately, by the beginning of September, rumours quickly spread that Portugal's stint on the UK's open list would prove brief, and that the country could be moved back to a mandatory quarantine list. Demand for flights out of Portugal to the UK surged. Meanwhile, the increase in foreign tourism bookings to Portugal that began in mid-August faltered by mid-September. These problems reflect a lack of a clear, predictable, and uniform process for applying border restrictions. To combat unpredictable and confusing restrictions by myriad individual governments, the European Commission is attempting to codify and unify the rules for travel restrictions, but no agreement has been reached. The hope of an even broader, global set of conditions for safe travel is even lower.

Regional discrepancies within countries

Croatia's experience in 2020 is reflective of another consideration as tourism recovers - the dichotomy of the rebound within individual countries. While Croatia's northern coasts have recovered somewhat in the third quarter, the southern coast lags badly. Not only are the southern regions farther to travel for central Europeans, but access to the region via road or rail requires that the traveller also cross the Bosnia-Herzegovina border. Typically, travelers to the south arrive via airlines or cruise ships. With activity on the former still struggling to return and the latter not yet beginning to revive, the southernmost areas of Croatia will greatly lag behind the rest of the country's tourist recovery. Elsewhere, other countries are reporting similar variances.

Over-reliance on certain pockets of arrivals

In Montenegro, a large share of its arrivals come from Russia. Many of those came in via package deals. During the COVID-19 pandemic, however, Montenegrin tourism has been affected by the fact that its borders were initially closed to Russia. Although Russia finally made it to the "green list" on 15 August, Moscow has not provided reciprocity. In fact, in a devastating blow to any hopes of boosting late-season revenues, Aeroflot announced in August that it was cancelling all flights to both Tivat Airport - the busiest Montenegrin airport, located on the coast - and to Dubrovnik Airport - also a key entry point to Montenegro - until March 2021. Similar challenges are present for other tourist destinations dependent upon a single large source of visitors.

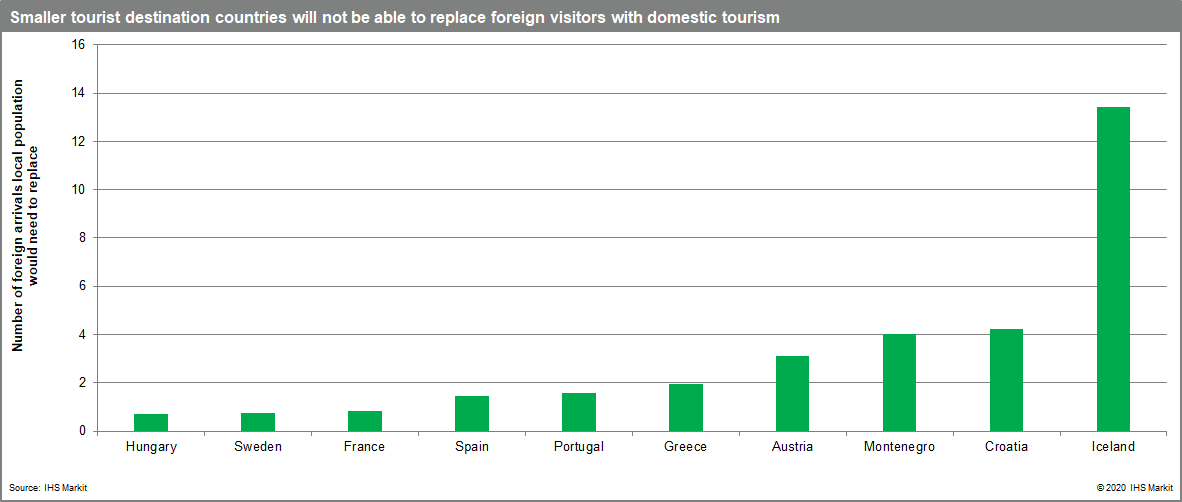

Replacement of foreign tourists with domestic travelers

One hope for rescuing the tourism sector is replacing foreign visitors with a surge in domestic travel. In Iceland, the government approved a package granting travel vouchers and other incentives for domestic tourism. Iceland's remote location enhances the importance of rescuing whatever domestic tourism income there might be. However, to make up for lost foreign visitors, each person living in Iceland would have to replace the spending of nearly 13.5 foreign visitors. The gaps are substantial in many other tourist countries as well, particularly the poorer economies of southeastern Europe. The wealthier, larger economies will be able to salvage a greater share of lost foreign arrivals by increasing domestic travel.

The recovery in 2020-21 and beyond

The UNWTO looked at previous shock events to global tourism - the 11 September 2001 attacks in the US, the outbreak of SARS in 2003, and the 2008 global market crash - and how quickly tourism losses faded. Tourism was down from year-earlier levels for between five and 10 months, only, in each of these shocks.

Our life sciences service maintains a current, baseline assumption that fully approved, effective vaccines will not be available to large parts of the global population until mid-2021. If we apply the 5-10 month recovery time estimated by the UNWTO, a return to more normal global tourism activity may not come until the first or second quarters of 2022. This suggests that, while there may be a rebound from the extreme contraction of tourism that we have seen in 2020, any recovery in 2021 in the tourism sector will be modest.

{"items" : [

{"name":"share","enabled":true,"desc":"<strong>Share</strong>","mobdesc":"Share","options":[ {"name":"facebook","url":"https://www.facebook.com/sharer.php?u=http%3a%2f%2fprod.azure.ihsmarkit.com%2fmarketintelligence%2fen%2fmi%2fresearch-analysis%2feuropean-tourism-lag-recovery-economy.html","enabled":true},{"name":"twitter","url":"https://twitter.com/intent/tweet?url=http%3a%2f%2fprod.azure.ihsmarkit.com%2fmarketintelligence%2fen%2fmi%2fresearch-analysis%2feuropean-tourism-lag-recovery-economy.html&text=European+tourism+will+lag+recovery+of+other+parts+of+the+economy+%7c+S%26P+Global+","enabled":true},{"name":"linkedin","url":"https://www.linkedin.com/sharing/share-offsite/?url=http%3a%2f%2fprod.azure.ihsmarkit.com%2fmarketintelligence%2fen%2fmi%2fresearch-analysis%2feuropean-tourism-lag-recovery-economy.html","enabled":true},{"name":"email","url":"?subject=European tourism will lag recovery of other parts of the economy | S&P Global &body=http%3a%2f%2fprod.azure.ihsmarkit.com%2fmarketintelligence%2fen%2fmi%2fresearch-analysis%2feuropean-tourism-lag-recovery-economy.html","enabled":true},{"name":"whatsapp","url":"https://api.whatsapp.com/send?text=European+tourism+will+lag+recovery+of+other+parts+of+the+economy+%7c+S%26P+Global+ http%3a%2f%2fprod.azure.ihsmarkit.com%2fmarketintelligence%2fen%2fmi%2fresearch-analysis%2feuropean-tourism-lag-recovery-economy.html","enabled":true}]}, {"name":"rtt","enabled":true,"mobdesc":"Top"}

]}