Customer Logins

Obtain the data you need to make the most informed decisions by accessing our extensive portfolio of information, analytics, and expertise. Sign in to the product or service center of your choice.

Customer Logins

BLOG

Nov 22, 2017

Assessing emerging risks in Sri Lanka's fast-developing banking sector

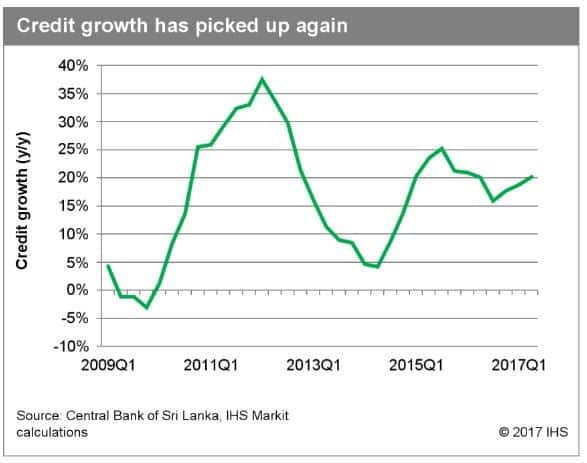

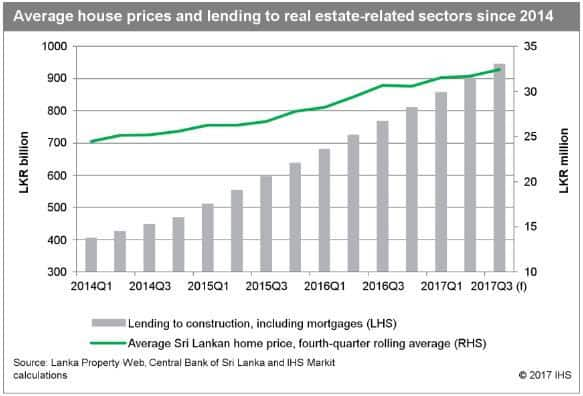

Sri Lanka's banking sector has grown rapidly since 2013, much of the growth witnessed in the last several years has been centered on construction and mortgage lending, yielding concerns that a house price correction episode could spell trouble for the sector's fast-growing banks. The stock of construction and mortgage lending by commercial banks increased by 21.8% year on year (y/y) in the second quarter of 2017, pushing it to account for 19.8% of total private-sector lending and 15% of total lending in the economy - the largest single sub-group. When licensed specialized banks (LSBs) are included , majority of which are mortgage banks, the banking sector's total exposure to construction and mortgages to 23% of total private-sector lending in the second quarter of 2017.

We judge that the rapid growth in lending to construction and mortgages is a source of near-term credit risk for the sector's banks, given recent concerns raised by Sri Lankan authorities regarding the health of the real estate sector . There has been little, if any, analysis from the government or the private sector of the risk from the housing market on the banking sector. While there is certainly interest in Sri Lanka's real estate market as a "land of opportunity" , it is also important to identify how much exposure banks have to the housing market and related real estate activities. IHS Markit has roughly three concerns: the lack of complete data affecting our ability to identify risk (such as house sale and sold price data), the currently missing macro-prudential policies on real estate loans, and whether the sales slowdown anecdotally reported for the capital, Colombo, is prevalent in other areas of the country.

Total "other LSBs" lending adds another 50% to construction and mortgage lending

Lending to construction and mortgages is overweight compared to the construction and real estate share of the country's gross value added (GVA), only at 15.8%. Historically, the banking sector has a somewhat imbalanced mortgage disbursement pattern with mortgage lending concentrated in the LSB sector . We find that after lending by "other LSBs" are included, lending to construction and mortgage lending jumps another 50%. Another concern is the government pro-construction policy since 2016, and considering that the government owns between 50% and 100% stakes in the three main "other LSBs": Housing Development Finance Corporation Bank of Sri Lanka (HDFC), National Savings Bank (NSB), and State Mortgage & Investment Bank (SMIB). They are likely to have implemented the government's policy to a further extent than private-sector counterparts.

Credit growth is fast for both construction and mortgage lending

By separating CBSL data into construction and mortgages, it shows that the year-on-year credit growth in the second quarter of 2017 for the construction industry alone was 26.0%, while mortgage lending, which includes construction for personal use, increased by 22.9%. Considering the data available, the rise in land prices is partly responsible for the rise in construction lending. Local property website Lanka Property Web, which tracks "for sale" prices of land and property, shows that residential land prices in Sri Lanka rose significantly in the third quarter of 2017, rising by 83% y/y. The rise in the raw input cost means more leverage is likely to be sought to build properties. Similarly, the website also shows that the annual asking price increase of houses and apartments combined rose 9% at the same time.

The lack of macro-prudential policies for real estate lending suggests the regulator's responsiveness

There is currently no macro-prudential regulation on real estate loans - mortgages, lending to construction, and lending to real estate companies - even though the CBSL has instituted loan-to-value (LTV) limits on motor vehicles. The risk management on mortgage and construction lending is therefore bank-dependent. Although there are signs from the central bank that it is becoming more concerned about risks from the housing market, there is still no policy to reduce the risk. In fact, the CBSL is only starting to study the risk from the sector now, with the hope that the yet-to-be-announced policies would be used to "slow" house price growth. Meanwhile, the government had opened up the sector in 2016 by allowing foreign investors to purchase properties in the country, in order to attract foreign currency and drive construction. This adds to the complexity of the housing market, and the Sri Lankan market will be more susceptible to a change in government policy or slowdown in economic growth of an investor's originating country.

Risks from real estate market concentrate in "high-end" Colombo market but are likely to spread nationally

According to Jones Lang-LaSalle, sales of high-end properties (concentrated in Colombo) in Sri Lanka have slowed from 25 per month to 10 following the comment made by the CBSL governor in July 2017. Lanka Property Web highlighted the land prices difference, with Colombo nearly eight times the average for Sri Lanka as a whole in 2017, a jump from four times between 2012-15. Because the slowdown in sales is reported only for high-end properties, a house price correction due to falling demand could be contained to just Colombo. The lack of data breakdown impedes our assessment of risk. However, considering anecdotal evidence suggesting that much of these high-end purchases are associated with the opening-up of the sector to foreign investment in 2016 and are driven by funds from China (closely related to the belt-and-road project), it is possible that the high-end market in Colombo is detached from the property market in the rest of country. Nonetheless, we still judge that there will be some reverberating effects on the rest of the country from the slowdown in Colombo.

Outlook and implications: Real estate lending should be a key area of focus for the regulator

Although the CBSL has been raising interest rates since 2016, this could not and should not be used to reduce risk alone; it is prudent to monitor risks forming in the sector and introduce related macro-prudential policies to counteract any risk build-up. A good example for Sri Lanka to follow is that of the Philippines, which has good data breakdown and a LTV ratio of 60% for housing loans to contain risk. The policy response in Sri Lanka is an area of interest as a significant downturn in that sector risks raising NPLs, reducing profitability, and eroding capital buffers.

Angus Lam is a Senior Economist for the Banking Risk service at IHS Markit

Posted 23 November 2017

{"items" : [

{"name":"share","enabled":true,"desc":"<strong>Share</strong>","mobdesc":"Share","options":[ {"name":"facebook","url":"https://www.facebook.com/sharer.php?u=http%3a%2f%2fprod.azure.ihsmarkit.com%2fmarketintelligence%2fen%2fmi%2fresearch-analysis%2fassessing-emerging-risks-in-sri-lankas-fast-developing-banking-sector.html","enabled":true},{"name":"twitter","url":"https://twitter.com/intent/tweet?url=http%3a%2f%2fprod.azure.ihsmarkit.com%2fmarketintelligence%2fen%2fmi%2fresearch-analysis%2fassessing-emerging-risks-in-sri-lankas-fast-developing-banking-sector.html&text=Assessing+emerging+risks+in+Sri+Lanka%27s+fast-developing+banking+sector","enabled":true},{"name":"linkedin","url":"https://www.linkedin.com/sharing/share-offsite/?url=http%3a%2f%2fprod.azure.ihsmarkit.com%2fmarketintelligence%2fen%2fmi%2fresearch-analysis%2fassessing-emerging-risks-in-sri-lankas-fast-developing-banking-sector.html","enabled":true},{"name":"email","url":"?subject=Assessing emerging risks in Sri Lanka's fast-developing banking sector&body=http%3a%2f%2fprod.azure.ihsmarkit.com%2fmarketintelligence%2fen%2fmi%2fresearch-analysis%2fassessing-emerging-risks-in-sri-lankas-fast-developing-banking-sector.html","enabled":true},{"name":"whatsapp","url":"https://api.whatsapp.com/send?text=Assessing+emerging+risks+in+Sri+Lanka%27s+fast-developing+banking+sector http%3a%2f%2fprod.azure.ihsmarkit.com%2fmarketintelligence%2fen%2fmi%2fresearch-analysis%2fassessing-emerging-risks-in-sri-lankas-fast-developing-banking-sector.html","enabled":true}]}, {"name":"rtt","enabled":true,"mobdesc":"Top"}

]}