Customer Logins

Obtain the data you need to make the most informed decisions by accessing our extensive portfolio of information, analytics, and expertise. Sign in to the product or service center of your choice.

Customer Logins

BLOG

Mar 25, 2019

Argentina is struggling to avoid a deeper recession

- The deepening of the recession calls for the loosening of the monetary policy; however, the inflation rate is still very high and not in a clear decelerating path, thus raising the risk of extreme volatility in the local currency.

- The IMF and Argentine authorities reached an agreement in March 2019 after the third review that requires a severe/faster fiscal spending adjustment aimed at reinforcing the SBA approved in 2018.

- The economy is in recession and confidence in the government's ability to push through severe adjustments is still weak. Breaking away from the vicious cycle of high devaluation and high inflation has proven quite difficult.

The Argentine peso showed appreciating pressure in January 2019, dropping below the Central Bank's (Banco Central de la República Argentina: BCRA) no-intervention range and prompting the bank to purchase hard currency and to relax monetary policy. However, the monthly inflation rate re-accelerated in February, leading the annual rate to be above 51%. Meanwhile, the manufacturing sector posted a double digit annual decrease in January. The tight credit conditions, the high cost of inputs, and the reduced demand are taking a toll on economic activity.

Faster monetary policy easing, déjà vu?

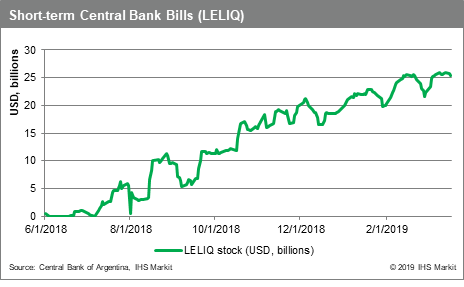

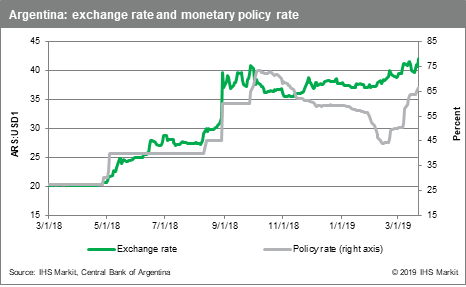

In December 2017 monetary authorities acknowledged their inability to reduce the inflation rate to the target and increased the target range; at the same time, the BCRA reduced the monetary policy rate. The sudden decline in the value of the Argentine peso in the first week of May 2018 prompted a series of measures that included raising the monetary policy rate to 40%. The government negotiated a Stand-by Arrangement with the International Monetary Fund (IMF) and secured funding. Nonetheless, the confidence crisis deepened, and the peso depreciated further in August-September 2018. The fast pass-through of the depreciation onto domestic prices quickly hiked up the consumer price index. The BCRA increased the policy rate to 60%. In addition, it changed its strategy to control liquidity by committing to freezing the monetary base (high-powered money) and by moving away from the USD-denominated instrument LEBAC to a peso-denominated LELIQ (which are short-term BCRA bills with rates currently determined by supply and demand for liquidity).The rollover of these instruments and the high interest rate have led to the significant increase in the amount of LELIQs in the past five months.

The urgency to reignite economic activity led to a rapid downwards adjustment in the LELIQs rate in mid-February 2019 (from 52.4% to 43.9%); in turn, like a knee-jerk reaction, the Argentine peso weakened quickly and the BCRA intervened by selling hard currency, despite the exchange rate being within the no-intervention range. Monetary authorities were uncomfortable with the pace of the depreciation and thus decided to intervene; the LELIQ rate bounced back to 50.2% in mid-February. Furthermore, after the failed attempt to lower the monetary policy rate monetary authorities pledged to continue freezing the monetary base until December 2019 and tightened monetary policy (the LELIQ rate increased to 66.65% by end-March 2019). These extreme interest rates are keeping credit in local currency down, with loans to the private sector declining in real terms in 2019. The high interest rates and the currency instability have led to an increase in the dollarization of credit in the banking system.

The outlook is bleak and finding the right mix of policies seems unlikely

Weaning off from the high interest rates, the easy/fast money wagon will continue to be a significant challenge for policymakers. Although authorities would like to reduce the incentive to park capital in the country's Central Bank instruments, the expectation of a still-high inflation rate requires a tight monetary policy approach despite the deep recession. The fast pass-through from currency depreciation to domestic prices is yet another hurdle to consider. Utility tariffs and other regulated items price increases along with annual wage adjustments will keep inflationary pressure up. Moreover, although the annual inflation rate is expected to progressively decelerate, it will remain above 40% until the third quarter of 2019. Breaking away from the vicious cycle of high devaluation and high inflation has proven quite difficult.

The Macri administration is under mounting pressure to restore economic growth before the presidential elections in October 2019. The risk of loosening the monetary policy too fast, before the inflation rate is on a more sustainable path, has temporarily diminished since the February currency volatility; however, it is still significant, and it will expose the country's vulnerabilities that have not been comprehensively dealt with since the 2018 confidence crisis. Although the government was able to reduce the overall fiscal deficit in real terms in 2018 it was mostly on the back of severe adjustments to capital spending; on the other hand, the public debt burden increased substantially as interest spending increased nearly 30% in real terms. The IMF and Argentine authorities reached an agreement in March 2019 after the third review that requires a severe/faster fiscal spending adjustment aimed at reinforcing the Stand-by agreement. However, social spending and subsidies to the private sectors are major sources of budget pressure and are not expected to be fully tackled in the short term given the upcoming elections. The outlook beyond 2019 is bleak. Neither of the possible alternatives would be able to immediately renege on the IMF agreement, as the softening of global economic growth implies difficulties in obtaining funding to support the fiscal deficit. If Macri is re-elected, we expect some tweaks and recalibrating of the current policies but not necessarily a full reform in terms of social spending.

{"items" : [

{"name":"share","enabled":true,"desc":"<strong>Share</strong>","mobdesc":"Share","options":[ {"name":"facebook","url":"https://www.facebook.com/sharer.php?u=http%3a%2f%2fprod.azure.ihsmarkit.com%2fmarketintelligence%2fen%2fmi%2fresearch-analysis%2fargentina-struggling-avoid-deeper-recession.html","enabled":true},{"name":"twitter","url":"https://twitter.com/intent/tweet?url=http%3a%2f%2fprod.azure.ihsmarkit.com%2fmarketintelligence%2fen%2fmi%2fresearch-analysis%2fargentina-struggling-avoid-deeper-recession.html&text=Argentina+is+struggling+to+avoid+a+deeper+recession+%7c+S%26P+Global+","enabled":true},{"name":"linkedin","url":"https://www.linkedin.com/sharing/share-offsite/?url=http%3a%2f%2fprod.azure.ihsmarkit.com%2fmarketintelligence%2fen%2fmi%2fresearch-analysis%2fargentina-struggling-avoid-deeper-recession.html","enabled":true},{"name":"email","url":"?subject=Argentina is struggling to avoid a deeper recession | S&P Global &body=http%3a%2f%2fprod.azure.ihsmarkit.com%2fmarketintelligence%2fen%2fmi%2fresearch-analysis%2fargentina-struggling-avoid-deeper-recession.html","enabled":true},{"name":"whatsapp","url":"https://api.whatsapp.com/send?text=Argentina+is+struggling+to+avoid+a+deeper+recession+%7c+S%26P+Global+ http%3a%2f%2fprod.azure.ihsmarkit.com%2fmarketintelligence%2fen%2fmi%2fresearch-analysis%2fargentina-struggling-avoid-deeper-recession.html","enabled":true}]}, {"name":"rtt","enabled":true,"mobdesc":"Top"}

]}