Customer Logins

Obtain the data you need to make the most informed decisions by accessing our extensive portfolio of information, analytics, and expertise. Sign in to the product or service center of your choice.

Customer Logins

BLOG

Oct 18, 2018

Argentina export tax and strike risks

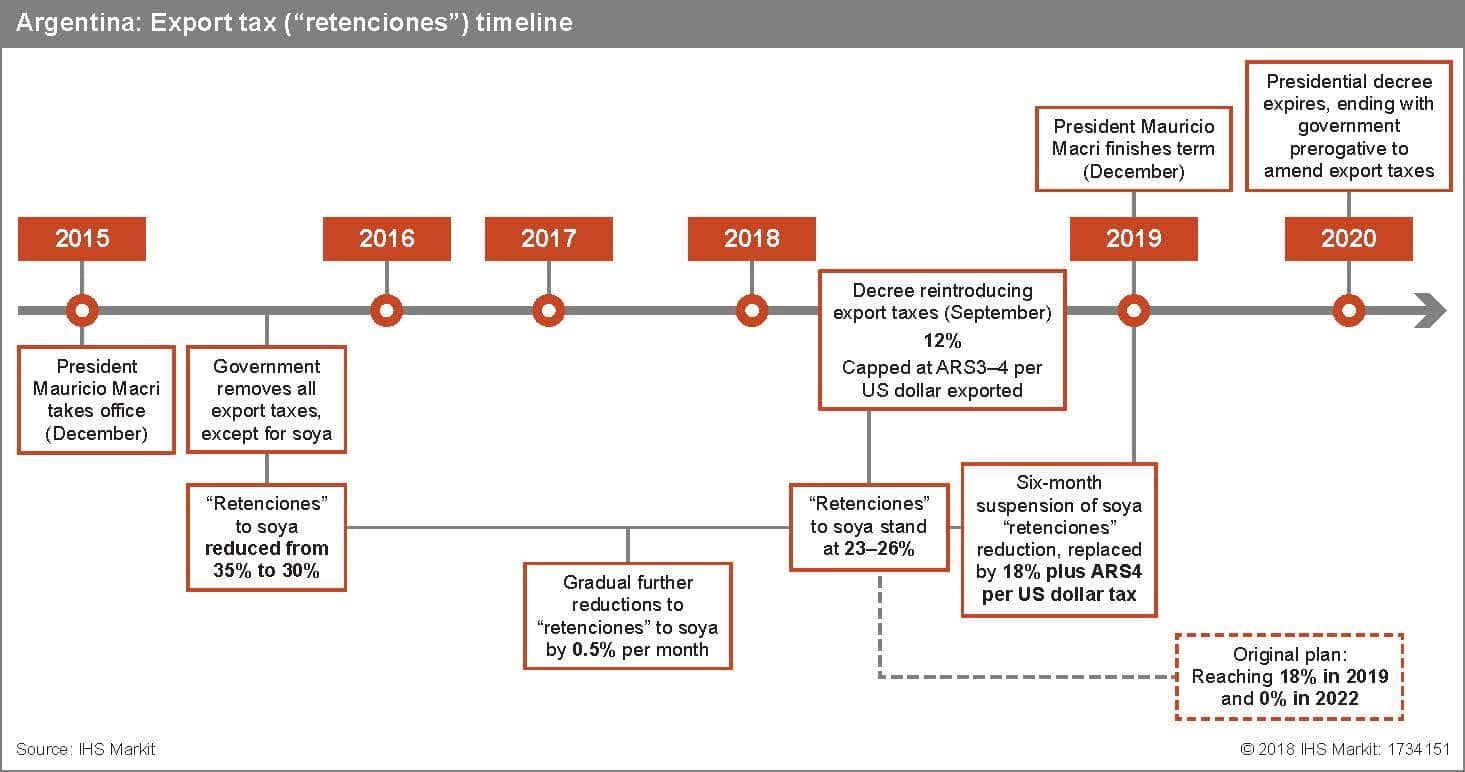

In September, President Mauricio Macri reinstated export taxes, seeking to meet a primary fiscal deficit target of 0% of GDP in 2019. Their revival represents a policy reversal since he had withdrawn them after taking office in 2015.

- Exports will be taxed at 12%, with a limit of ARS3-4 per US dollar exported, and the government will maintain the prerogative to introduce further changes up to 2020 to reflect its fiscal needs.

- Agribusiness exports have expanded their value in local currency terms because of peso depreciation against the US dollar.

- Rising unemployment and continuing high inflation risk triggering labour strikes, disrupting supply chains, and port operations in the coming year.

On 10 October 2018, Argentina's agricultural trade associations Acsoja, Asagir, ArgenTrigo, and Maizar (which include soya, maize, wheat, sorghum, and sunflower producers and exporters) issued a statement criticizing the 2019 Budget and a September presidential decree permitting the government to apply export taxes ('retenciones') of up to 33% until 2020. President Mauricio Macri is focused on reducing Argentina's primary fiscal deficit to 0% of GDP in 2019, as part of the framework for the expanded Stand-by-Arrangement (SBA) with the International Monetary Fund (IMF). Within this fiscal drive, Macri has reinstated some export taxes, such as those on maize and wheat that he eliminated upon taking office in 2015, while freezing for six months the calendar to phase out export taxes on soya. The government estimates that export taxes should provide additional revenue worth 0.5% of GDP in 2018 and 1.5% in 2019. Macri has insisted that the taxes will only be temporary.

Under the new system, exports will be taxed an additional 12%, with a limit of ARS4 per USD1 exported for those products with a low added value such as mining, oil and gas, and grains. Taxes for more elaborate products such as metallurgic products, automobiles, and technology will be capped at ARS3 per USD1. Soya exports were being taxed at 35% when Macri took office, with this level being reduced immediately to 30% and then gradually by a further 0.5% monthly since January 2018. The new system would leave soya export tax at 18%, plus ARS4 per USD1. According to private estimates quoted in the Argentine media this translates into a 29% tax (above the 23-26% level implied when the measure was implemented), using an exchange rate of ARS40/USD1.

Export growth and stronger trade balance expected by authorities

The Argentine peso has depreciated by 50% since the beginning of the year. The government is expecting peso depreciation to help reverse the trade deficit, which reached a record deficit in 2017 of USD8.5 billion, and permit a trade surplus of USD5.8 billion for 2019 (with a 19% increase in the value of exports and 2.3% increase in the value of imports). The improving trade balance is projected to come mainly from the agribusiness sector, the development of unconventional gas field Vaca Muerta in the southern Neuquén province, and industrial manufacturing (mainly cars).

Mixed outlook for exporters

The agribusiness sector - which contributes to approximately 10% of Argentina's GDP and 65% of its exports - has benefited from the peso depreciation, mitigating the economic burden of the new tax. The prices of agricultural products in the local market have increased since April 2018, including increases for soya beans (by 53%), wheat (77%), and maize (49%). The sector also expects a record harvest of at least 130 million tons for 2018-19 (subject to favorable weather conditions), approximately a 30% increase compared with the previous year. This would leave some 95 million tons available for export, which would yield foreign-exchange earnings of USD25 billion for Argentina. The sector is recovering from a severe drought which damaged the 2017-18 harvest, causing an estimated USD6-billion reduction in soya and maize exports and contributing significantly to the contraction of 5.8% in GDP year on year recorded in May 2018.

In energy, the downstream sector has been affected by shrinkage of the domestic market and a fall in economic activity due to high inflation (forecast by IHS Markit at 41% in 2018) and record-high local policy interest rates (60%). By contrast, upstream and export sectors have benefited from higher earnings margins in pesos per US dollar exported. Since the beginning of Macri's term (December 2015), the price of Brent oil per barrel has increased by 113% (from USD38 to USD81). Coupled with peso depreciation, this generates more incentives for investment in unconventional oil and gas development, particularly shale gas and tight oil deposits in Vaca Muerta, a sector where the government is actively looking for investment. Mining companies have criticized the new taxes, flagging an average 17% decline in their share prices following the announcement. In 2015, the government removed a 10% export tax for mining, which has now been restored at a rate of ARS4 per USD1.

Industries such as the metallurgic, automobile, chemicals, and pharmaceuticals will see their costs increase because of the stronger dollar as they import 40-70% of the inputs required for local production. However, the negative effect in skilled-labor-intensive sectors, such as mining, upstream energy, the industrial sector, and pharmaceuticals, will be partly compensated by lower labor costs, which are paid in pesos despite large companies calculating profits in US dollars.

Outlook and implications

The introduction of a free-floating band in early October - which allows the Central Bank of Argentina to intervene only if the peso fluctuates outside the band of ARS34-44/USD1 - has helped stabilize the peso, which has maintained an average of ARS38/USD1 so far in October. However, IHS Markit expects further peso depreciation, to reach ARS41/USD1 by end-2018, and ARS49/USD1 by end-2019. This means that exchange-rate movements will continue to favor exporters, particularly relative to the exchange rate in 2017 (ARS19/USD1), which discouraged exports, leading to Argentina's overall trade deficit.

However, the export sector will face increased risks of labor strikes, encouraged by worsening unemployment (forecast at 10.1% for 2018 by IHS Markit, up from 8.3% in 2017), high inflation and increases in fuel prices. Labor disputes are likely to disrupt supply chains affecting the export sector. In particular, strikes by truck drivers and port workers will cause delays to exports, particularly at the port hub of Rosario, and increase operating costs for exporters. The likelihood of labor strikes to increase pressure on the government will remain high over the coming year, as the economic situation is unlikely to improve. Argentina's economy is already in recession, and IHS Markit forecasts a contraction by 2.3% of GDP in 2018 and 1.7% of GDP in 2019. Although protests and strikes are unlikely to derail the government's efforts to reduce the fiscal deficit, increased political pressure is likely to slow the implementation of spending cuts.

A reduction in strike risks would be indicated if the government succeeds in lowering inflation in the coming months, in turn easing union demands for wage increases. A prolific harvest in the first quarter of 2019 would indicate boosted exports, also serving as an indicator of more positive economic growth and peso stabilization.

{"items" : [

{"name":"share","enabled":true,"desc":"<strong>Share</strong>","mobdesc":"Share","options":[ {"name":"facebook","url":"https://www.facebook.com/sharer.php?u=http%3a%2f%2fprod.azure.ihsmarkit.com%2fmarketintelligence%2fen%2fmi%2fresearch-analysis%2fargentina-export-tax-and-strike-risks.html","enabled":true},{"name":"twitter","url":"https://twitter.com/intent/tweet?url=http%3a%2f%2fprod.azure.ihsmarkit.com%2fmarketintelligence%2fen%2fmi%2fresearch-analysis%2fargentina-export-tax-and-strike-risks.html&text=Argentina+export+tax+and+strike+risks+%7c+S%26P+Global+","enabled":true},{"name":"linkedin","url":"https://www.linkedin.com/sharing/share-offsite/?url=http%3a%2f%2fprod.azure.ihsmarkit.com%2fmarketintelligence%2fen%2fmi%2fresearch-analysis%2fargentina-export-tax-and-strike-risks.html","enabled":true},{"name":"email","url":"?subject=Argentina export tax and strike risks | S&P Global &body=http%3a%2f%2fprod.azure.ihsmarkit.com%2fmarketintelligence%2fen%2fmi%2fresearch-analysis%2fargentina-export-tax-and-strike-risks.html","enabled":true},{"name":"whatsapp","url":"https://api.whatsapp.com/send?text=Argentina+export+tax+and+strike+risks+%7c+S%26P+Global+ http%3a%2f%2fprod.azure.ihsmarkit.com%2fmarketintelligence%2fen%2fmi%2fresearch-analysis%2fargentina-export-tax-and-strike-risks.html","enabled":true}]}, {"name":"rtt","enabled":true,"mobdesc":"Top"}

]}