Customer Logins

Obtain the data you need to make the most informed decisions by accessing our extensive portfolio of information, analytics, and expertise. Sign in to the product or service center of your choice.

Customer Logins

BLOG

Nov 02, 2018

Another IMF bailout for Pakistan

- Pakistan's newly elected PTI government formally requested IMF financial assistance on 11 October after it exhausted alternative options to close its sizeable external liquidity gap. If approved, the measure would be the 13th IMF bailout program to Pakistan since 1988.

- The new IMF package would ease immediate liquidity pressures, but Pakistan's high level of external debt and rollover risk will still weigh on the country's solvency in the three-year outlook.

- Compliance is also likely to prove politically difficult, given the risk of domestic protests and pushback from coalition partners, thus increasing the risk of incomplete IMF disbursement, government instability, and debt renegotiation.

An economic "Déjà Vu", with a twist

Two years after a successful completion of the previous IMF

program in October 2016, Pakistan's external and public finances

have once again been compromised by a rapid widening of the current

account and fiscal deficits and a swift accumulation of external

and public debt. The current account deficit soared to USD14.3

billion in the first nine months of 2018, more than doubling from

the full-year level of 2016, while fiscal deficit reached 6.6% of

GDP in the financial year ending June 2018, overshooting the target

by over a full percentage point.

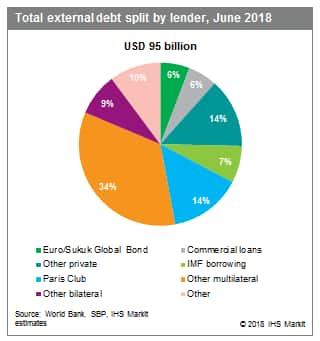

While all too familiar to Pakistan, the external and fiscal

problems have been further exacerbated by a large increase in

infrastructure investment as part of the China-Pakistan Economic

Corridor (CPEC) program. Largely financed through Chinese

government and commercial loans, it exerted severe pressure on

Pakistan's economy through increased imports, government spending,

and external borrowing. Since 2015, Pakistan added over USD30

billion to its external debt stock, standing at USD95.1 billion at

end-June 2018 (an estimated 34% of GDP).

Possible stumbling blocks in negotiations with the IMF

The formal request for the IMF loan in early October coincided with the rupee devaluation by the State Bank of Pakistan, the sixth in the last fifteen months. After depreciating by over 20% since December 2017, the rupee remains overvalued, and greater exchange rate flexibility will be among the key IMF conditions for a new loan. As in the previous programs, the Fund will also insist on structural fiscal and energy-sector reforms.

A new element of the upcoming program may be an IMF request for greater disclosure of foreign loans by Pakistan. This measure would seek increased transparency over CPEC-related lending by China. Although this is a possible area of contention, the issue is unlikely to block an agreement altogether, particularly since most of Pakistan's USD9.3-billion external debt service obligations due in FY 2018-19 are maturing sovereign bond repayments and debt payments to the IMF itself.

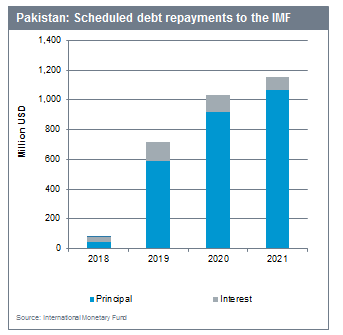

Can Pakistan still default on its external obligations?

The program will ease immediate liquidity pressures and facilitate additional lending from other international institutions. Nevertheless, solvency risks will remain high: between 2019 and 2022, Pakistan faces heavy debt service burdens from conventional bonds and sukkuk issuance since 2014, as well as principal repayments on previous IMF loans. In addition, we assess that at least some of Pakistan's private-sector debt is still at risk of rescheduling. In August, IHS Markit Sovereign Risk Service downgraded Pakistan's medium-term sovereign risk to 65 points (CCC+ on the generic scale) with a negative outlook. Obtaining a new IMF loan would return the country's outlook to Stable, but any rating upgrade would greatly depend on the government's ability to reduce systemic sources of external and public debt accumulation.

Public opposition to IMF conditions

The IMF call for fiscal reforms, namely the requests to cut energy subsidies and privatize inefficient state-owned companies - notably Pakistan International Airlines, Pakistan Steel Mills, and several electricity distribution firms - are likely to prove difficult to implement politically, given broad public opposition. This threatens to generate violent social unrest in Pakistan's urban areas over the three-year outlook, including in the cities of Islamabad, Lahore, and Karachi.

The government's response to such protests would indicate whether Pakistan is able to access the IMF loan in full and would also indicate the stability of the government itself. Prime Minister Imran Khan has already demonstrated flexibility in his polices when facing popular demand. Most notably, under the popular pressure the government scaled down the initially announced reduction in gas subsidies in September. Moreover, unlike the previous government, the PTI administration relies on its coalition partners to retain power; we assess that this will significantly reduce the government's scope to successfully implement IMF conditions, with coalition partners likely to oppose some of these measures. In addition, although the previous IMF loan to Pakistan was completed despite breaching several conditions - including subsidy cuts and privatization - a deterioration in US-Pakistan relations indicates reduced flexibility under a new IMF facility.

{"items" : [

{"name":"share","enabled":true,"desc":"<strong>Share</strong>","mobdesc":"Share","options":[ {"name":"facebook","url":"https://www.facebook.com/sharer.php?u=http%3a%2f%2fprod.azure.ihsmarkit.com%2fmarketintelligence%2fen%2fmi%2fresearch-analysis%2fanother-imf-bailout-pakistan.html","enabled":true},{"name":"twitter","url":"https://twitter.com/intent/tweet?url=http%3a%2f%2fprod.azure.ihsmarkit.com%2fmarketintelligence%2fen%2fmi%2fresearch-analysis%2fanother-imf-bailout-pakistan.html&text=Another+IMF+bailout+for+Pakistan+%7c+S%26P+Global+","enabled":true},{"name":"linkedin","url":"https://www.linkedin.com/sharing/share-offsite/?url=http%3a%2f%2fprod.azure.ihsmarkit.com%2fmarketintelligence%2fen%2fmi%2fresearch-analysis%2fanother-imf-bailout-pakistan.html","enabled":true},{"name":"email","url":"?subject=Another IMF bailout for Pakistan | S&P Global &body=http%3a%2f%2fprod.azure.ihsmarkit.com%2fmarketintelligence%2fen%2fmi%2fresearch-analysis%2fanother-imf-bailout-pakistan.html","enabled":true},{"name":"whatsapp","url":"https://api.whatsapp.com/send?text=Another+IMF+bailout+for+Pakistan+%7c+S%26P+Global+ http%3a%2f%2fprod.azure.ihsmarkit.com%2fmarketintelligence%2fen%2fmi%2fresearch-analysis%2fanother-imf-bailout-pakistan.html","enabled":true}]}, {"name":"rtt","enabled":true,"mobdesc":"Top"}

]}